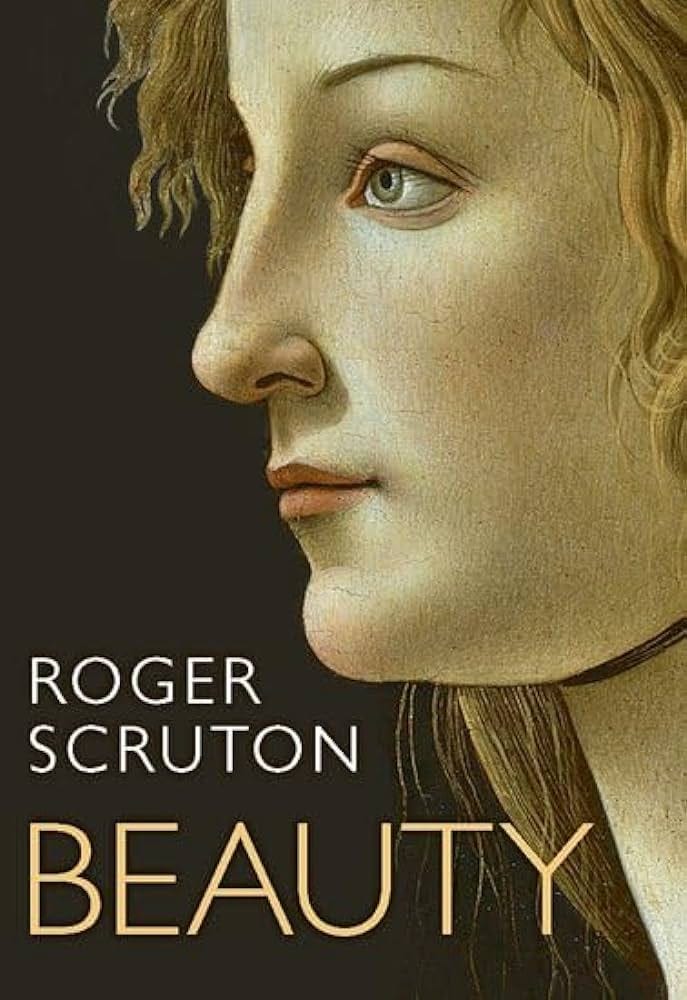

Chapter 1 of Roger Scruton's Beauty explores the complex notion of "judging beauty" across a wide range of objects and experiences. Scruton begins by reflecting on the ubiquity and variety of beauty, noting that beauty is recognized in both concrete objects and abstract ideas, from natural phenomena to human creations. This breadth challenges the idea that beauty is a simple, singular property; instead, it is a multifaceted concept that intersects with both the sensory and intellectual domains.

Scruton revisits classical and philosophical perspectives on beauty, linking it to the transcendentals—truth, goodness, and beauty—which were historically seen as ultimate values pursued for their own sake. This tradition, rooted in the works of Plato and incorporated into Christian thought by figures like Aquinas, frames beauty as an intrinsic value that commands attention and contemplation without requiring justification.

However, Scruton acknowledges the modern skepticism towards such a unified view of beauty. He points out that beauty can sometimes conflict with truth or goodness, suggesting a more complex relationship than classical ideals might suggest. For instance, a beautiful myth might tempt one to believe it despite its falsehood, or the beauty of a person might lead one to overlook their moral failings.

The chapter delves into the judgment of beauty as an expression of a state of mind, reflecting personal and cultural aesthetics rather than objective standards. This subjectivity is central to understanding beauty in contemporary terms, where aesthetic judgments often blend personal experiences with broader cultural influences.

Ultimately, Scruton sets the stage for a philosophical inquiry into beauty that respects its historical depth while acknowledging the nuances and challenges of contemporary interpretation. This exploration is intended not just to recount philosophical theories but to actively engage the reader in questioning and redefining their own perceptions of beauty.

Quotes

1.) Beauty may be an ultimate value along with truth and goodness.

There is an appealing idea about beauty which goes back to Plato and Plotinus, and which became incorporated by various routes into Christian theological thinking. According to this idea beauty is an ultimate value—something that we pursue for its own sake, and for the pursuit of which no further reason need be given. Beauty should therefore be compared to truth and goodness, one member of a trio of ultimate values which justify our rational inclinations.

2.) Truth and Goodness don’t seem to conflict while beauty may conflict with truth and goodness as when we overlook bad character in a beautiful woman.

From Kierkegaard to Wilde the ‘aesthetic’ way of life, in which beauty is pursued as the supreme value, has been opposed to the life of virtue…The status of beauty as an ultimate value is questionable, in the way that the status of truth and goodness are not.

3.) Plotinus argued that beauty was an attribute of God.

In the Enneads of Plotinus, that truth, beauty and goodness are attributes of the deity, ways in which the divine unity makes itself known to the human soul.

4.) There are six main Platitudes of Beauty we intuitively accept to be true:

(Beauty pleases us.

One thing can be more beautiful than another

Beauty is always a reason for attending to the thing that possesses it.

Beauty is the subject-matter of a judgement: the judgement of taste.

The judgement of taste is about the beautiful object, not about the subject’s state of mind. In describing an object as beautiful, I am describing it, not me.

Nevertheless, there are no second-hand judgements of beauty. There is no way that you can argue me into a judgement that I have not made for myself, nor can I become an expert in beauty, simply by studying what others have said about beautiful objects, and without experiencing and judging for myself. This last platitude can be doubted.

5.) Taste can be educated and refined so that we learn to see the “right” things as beautiful.

We distinguish true beauty from fake beauty—from kitsch, schmaltz and whimsy. We argue about beauty, and strive to educate our taste.

The judgement of taste is a genuine judgement, one that is supported by reasons. But these reasons can never amount to a deductive argument.

6.) The Paradox of Beauty: We can acknowledge reasons why something could be seen as beautiful without finding it beautiful ourselves.

Reasons support our judgement by providing a rationale for why we find something beautiful. For instance, we might find a painting beautiful because of its use of colors and composition. However, these reasons do not compel the judgement of beauty. In other words, someone else may not find the same painting beautiful despite acknowledging the reasons provided (like color use and composition).

7.) Minimal Beauty refers to the lowest degree of beauty that pleases us such has having a tidy room.

“A minimal beauty—beauty in the lowest degree, which might be a long way from the ‘sacred’ beauties of art and nature which are discussed by the philosophers. There is an aesthetic minimalism exemplified by laying the table, tidying your room, designing a web-site, which seems at first sight quite remote from the aesthetic heroism exemplified by Bernini’s St Teresa in Ecstasy or Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. You don’t wrestle over these things as Beethoven wrestled over the late quartets, nor do you expect them to be recorded for all time among the triumphs of artistic achievement. Nevertheless, you want the table, the room or the web-site to look right, and looking right matters in the way that beauty generally matters—not by pleasing the eye only, but by conveying meanings and values which have weight for you and which you are consciously putting on display.

Much that is said about beauty and its importance in our lives ignores the minimal beauty of an unpretentious street, a nice pair of shoes or a tasteful piece of wrapping paper, as though those things belonged to a different order of value from a church by Bramante or a Shakespeare sonnet. Yet these minimal beauties are far more important to our daily lives, and far more intricately involved in our own rational decisions, than the great works which (if we are lucky) occupy our leisure hours.

8.) Minimal Beauty is important as it enhances great works of art.

Were we to aim in every case at the kind of supreme beauty exemplified by Sta Maria della Salute, we should end with aesthetic overload. The clamorous masterpieces, jostling for attention side by side, would lose their distinctiveness, and the beauty of each of them would be at war with the beauty of the rest.

9.) Beauty is an end in itself and is related to leisure and play.

We appreciate beautiful things not for their utility only, but also for what they are

in themselves—or more plausibly, for how they appear in themselves. ‘With the good, the true and the useful,’ wrote Schiller, ‘man is merely in earnest; but with the beautiful he plays.’

When our interest is entirely taken up by a thing, as it appears in our perception, and independently of any use to which it might be put, then do we begin to speak of its beauty.

10.) The fine arts are distinguished from useful arts or “crafts” in that fine arts are about beauty first while useful arts are about utility.

The thought here gave rise in the eighteenth century to an important distinction between the fine and the useful arts. Useful arts, like architecture, carpet-weaving and carpentry, have a function, and can be judged according to how well they fulfil it. But a functional building or carpet is not, for that reason, beautiful.

In wrestling with the distinction between the fine and useful arts (les beaux arts et les arts utiles) Enlightenment thinkers made the first steps towards our modern conception of the work of art, as a thing whose value resides in it and not in its purpose.

Other epochs did not recognize the distinction that we now so frequently make between art and craft. Our word ‘poetry’ comes from Greek poiesis, the skill of making things; the Roman artes comprised every kind of practical endeavour.

11.) The desire for beauty cannot ever be satisfied as we want to contemplate it continually. When something is beautiful we want “it” and not to do something with it.

One thing that would explain this state of mind is the judgement of beauty: ‘I want that peach because it is so beautiful.’ Wanting something for its beauty is wanting it, not wanting to do something with it. Nor, having obtained the peach, held it, turned it around, studied it from every angle, would it be open to Rachel to say ‘good, that’s it, I’m satisfied’. If she had wanted it for its beauty then there is no point at which her desire could be satisfied, nor is there any action, process or whatever, following which the desire is over and done with. She can want to inspect the peach for all sorts of reasons, even for no reason at all. But wanting it for its beauty is not wanting to inspect it: it is wanting to contemplate it— and that is something more than a search for information or an expression of appetite. Here is a want without a goal: a desire that cannot be fulfilled since there is nothing that would count as its fulfilment.

12.) Modern architecture prioritizes function over beauty and gives little regard to beauty itself.

The architect Louis Sullivan went further, arguing that beauty in architecture (and by implication in the other useful arts) arises when form follows function. In other words, we experience beauty when we see how the function of a thing generates and is expressed in its observable features. The slogan ‘form follows function’ thereafter became a kind of manifesto, persuading a whole generation of architects to treat beauty as a by-product of functionality, rather than (what it had been for the Beaux-Arts school against which Sullivan was in rebellion) the defining goal.

13.) Beautiful buildings last forever and its function changes while merely functional buildings get torn down.

Beautiful buildings change their uses; merely functional buildings get torn down. Sancta Sophia in Istanbul was built as a church, became a barracks, then a stable, then a mosque and then a museum.

14.) Some view beauty as a purely sensory experience while others see it as an intellectual judgment.

There is an ancient view that beauty is the object of a sensory rather than an intellectual delight, and that the senses must always be involved in appreciating it. Hence, when the philosophy of art became conscious of itself at the beginning of the eighteenth century, it called itself ‘aesthetics’, after the Greek aisthe¯sis, sensation. When Kant wrote that the beautiful is that which pleases immediately, and without concepts he was providing a rich philosophical embellishment to this tradition of thinking. Aquinas too seems to have endorsed the idea, defining the beautiful in the first part of the Summa as that which is pleasing to sight.

15.) Ruskin distinguished between aesthesis which is pure sensory enjoyment and theoria which adds contemplation to sensory enjoyment.

The issue here might seem to be simple: is the pleasure in beauty a sensory or an intellectual pleasure? But then, what is the difference between the two? The pleasure of a hot bath is sensory; the pleasure of a mathematical puzzle intellectual. But between those two there are a thousand intermediary positions, so that the question of where aesthetic pleasure lies on the spectrumhas become one of themost vexed issues in aesthetics. Ruskin, in a famous passage of Modern Painters, distinguished merely sensuous interest, which he called aesthesis, from the true interest in art, which he called theoria, after the Greek for contemplation—not wishing, however, to assimilate art to science, or to deny that the senses are intimately involved in the appreciation of beauty.

16.) Taste and smell cannot rise to the level of theoria but are purely sensual pleasures.

Tastes and smells are not capable of the kind of systematic organization that turns sounds into words and tones. We can relish them, but only in a sensual way that barely engages our imagination or our thought. They are, so to speak, insufficiently intellectual to prompt the interest in beauty.

17.) The judgment of beauty is related to having a “disinterested interest” in the beautiful thing itself.

It is difficult to date the rise of modern aesthetics precisely. But it is undeniable that the subject took a great step forward with the Characteristics (1711), of the third Earl of Shaftesbury, a pupil of Locke and one of the most influential essayists of the eighteenth century. In that work Shaftesbury explained the peculiar features of the judgement of beauty in terms of the disinterested attitude of the judge. To be interested in beauty is to set all interests aside, so as to attend to the thing itself….It is an interest of reason itself.

One sign of a disinterested attitude is that it does not regard its object as one among many possible substitutes.

Explanation: In aesthetics, being disinterested means that our judgment of beauty is not influenced by personal gain, practical considerations, or emotions like desire or fear. When we approach something with disinterestedness, we are able to appreciate it purely for its aesthetic qualities rather than for any external or personal reasons. Despite the term "disinterested," it does not imply a lack of interest or engagement with the object of aesthetic judgment. Instead, it suggests an interest that is detached from personal or pragmatic concerns. This type of interest focuses solely on the aesthetic experience itself—how the artwork or object affects our senses and emotions purely on the grounds of its beauty or artistic merit.

18.) We can distinguish pleasure from, pleasure in and pleasure that….

Pleasure From: This refers to the pleasure derived from the external effects or consequences of something. For example, the pleasure one experiences from a warm bath is due to the physical sensation of warmth and relaxation it provides. It is a direct result of the sensory experience without deeper contemplation or thought about the bath itself.

Pleasure In: "Pleasure in" refers to a more nuanced form of enjoyment that involves a deeper engagement with the object or experience. In the context of aesthetics, it specifically denotes the pleasure derived from contemplating or appreciating the qualities and properties of something, such as a work of art or natural beauty. This type of pleasure is not purely sensory or superficial. Instead, it involves a cognitive or emotional connection to the object, where one finds satisfaction in its aesthetic qualities, emotional resonance, or intellectual stimulation.

"Pleasure that" refers to pleasure derived from the fact or knowledge about something rather than direct engagement with it. It emphasizes the pleasure derived from knowing or understanding a fact, event, or concept. An example could be the pleasure derived from knowing the historical significance of an artwork or understanding the complex symbolism within it, which enhances one's appreciation of its beauty or meaning.

19.) Beauty is also linked to curiosity as we seek to understand more about beautiful things.

Like the pleasure of friendship, the pleasure in beauty is curious: it aims to understand its object, and to value what it finds

20.) Kant believed beauty was a universal subjective experience in that people with similar qualities and taste would agree.

Explanation: Kant argues that judgments of taste, such as declaring something beautiful, are inherently subjective. They reflect an individual's personal aesthetic experience and sensibility.

Despite being subjective, Kant suggests that when someone makes a judgment of taste, they present it as if it has a universal validity. In other words, when we declare something beautiful, we often express it in a manner that suggests others, if they perceive it correctly or have refined taste, would agree with our judgment.

When we describe something as beautiful, we are not merely expressing our feelings or subjective experience towards it. Instead, we are making a claim about the object itself—asserting that it possesses qualities that warrant its designation as beautiful.

This claim implies an expectation or belief that others, upon perceiving the same object in the same way (if they see things aright), would agree with our judgment of its beauty.

Kant's idea does not imply that aesthetic judgments are objectively binding on everyone in an absolute sense. Rather, it suggests that aesthetic judgments can achieve a kind of intersubjective agreement or consensus among individuals who share similar perceptual and cognitive capacities.

Chapter 2 - Human Beauty

Scruton begins by exploring the idea that human beauty is often seen as a special category, distinct from other forms of beauty found in nature or art. He emphasizes that human beauty is deeply tied to personal and cultural contexts, and is often linked to moral and spiritual dimensions.

The Sacred and the Beautiful

Scruton draws a connection between the experience of beauty and the sacred. He suggests that human beauty has a unique capacity to evoke a sense of the sacred, a reverence that places the beautiful person in a realm beyond mere physical attraction. This idea is illustrated with references to religious art, such as images of the Virgin Mary, which symbolize purity and divine beauty.

Beauty and Charm

The chapter discusses the gradations of beauty, noting that not all attractive people are considered 'beautiful' in the highest sense. Scruton introduces the idea of charm and other lesser degrees of beauty, which still elicit a positive response but do not reach the level of the sublime or the divine.

Disinterested Interest

Scruton revisits the concept of 'disinterested interest' in beauty, suggesting that even in the context of sexual attraction, beauty is appreciated for how it presents itself to the mind, rather than as an object of possession. He argues that the judgment of beauty remains contemplative, focusing on the individual's form and presence rather than purely on physical desire.

Beauty and Sexual Desire

Scruton acknowledges that beauty often inspires desire, but he distinguishes between the desire for the individual and the contemplation of their beauty. He suggests that beauty elevates desire, transforming it from mere physical attraction to a more profound appreciation of the person's individuality and spirit.

Beauty as Embodiment

Human beauty, according to Scruton, is deeply connected to the idea of embodiment. It is not just about physical features but about the expression of the soul through the body. This is why certain features like the eyes, mouth, and hands are universally appealing—they are the windows through which the soul is perceived.

The Beautiful Soul

Drawing on philosophical traditions, particularly Hegel's concept of the 'beautiful soul', Scruton explores how beauty is not just a physical attribute but also a moral and spiritual one. A beautiful soul is perceived through actions, expressions, and the moral presence of an individual.

The Moral Dimension of Beauty

Scruton discusses the moral implications of beauty, suggesting that true beauty inspires a sense of respect and reverence. This respect extends to how we perceive and interact with beautiful people, recognizing their dignity and individuality.

Evolutionary Psychology and Beauty

The chapter also touches on evolutionary psychology's perspective on beauty, particularly the idea that beauty may have evolved as a signal of reproductive fitness. However, Scruton is critical of reducing beauty to purely biological terms, arguing that human appreciation of beauty involves rational and moral dimensions that go beyond mere physical attraction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Scruton presents human beauty as a complex interplay of physical, moral, and spiritual elements. It is an experience that transcends mere physical attraction, inviting a contemplative appreciation that respects the individual's dignity and uniqueness.

Quotes and Principles

1.) Beauty in humans may signal reproductive fitness just as the peacock who shows his feathers.

According to this theory the sense of beauty has emerged through the process of sexual selection—a suggestion originally made by Darwin in The Descent of Man. As augmented by Miller, the theory suggests that by making himself beautiful the man is doing what the peacock does when he displays his tail: he is giving a sign of his reproductive fitness, to which a woman responds as the peahen responds, claiming him (though in no way conscious that she is doing this) on behalf of her genes.

2.) A 7th platitude of beauty is: Beauty, in a person, prompts desire.

Your eyes are captivated by the beautiful boy or girl, and it is from this moment that your desire begins. It may be that there is another and maturer form of sexual desire, which grows from love, and which finds beauty in the no longer youthful features of a lifelong companion. But that is emphatically not the phenomenon that Plato had in mind

3.) “In the realm of art beauty is an object of contemplation, not desire.”

4.) According to Plato, physical desire is a lower form of love and contemplation of beauty is the higher form we must strive for.

Plato was drawn to the second of those responses. He identified eros as the origin of both sexual desire and the love of beauty. Eros is a form of love which seeks to unite with its object, and to make copies of it—as men and women make copies of themselves through sexual reproduction. In addition to that base form (as Plato saw it) of erotic love, there is also a higher form, in which the object of love is not possessed but contemplated, and in which the process of copying occurs not in the realm of concrete particulars but in the realm of abstract ideas—the realm of the ‘forms’ as Plato described them. By contemplating beauty the soul rises from its immersion in merely sensuous and concrete things, and ascends to a higher sphere, where it is not the beautiful boy who is studied, but the form of the beautiful itself, which enters the soul as a true possession, in the way that ideas generally reproduce themselves in the souls of those who understand them. This higher form of reproduction belongs to the aspiration towards immortality, which is the soul’s highest longing in this world. But it is impeded by too great a fixation on the lower kind of reproduction, which is a form of imprisonment in the here and now.

5.) Plato teaches that ordinary sexual desire binds us to the transient aspects of the world, while love of beauty urges us to transcend sensory attachments.

According to Plato, sexual desire, in its common form, involves a desire to possess what is mortal and transient, and a consequent enslavement to the lower aspect of the soul, the aspect that is immersed in sensuous immediacy and the things of this world. The love of beauty is really a signal to free ourselves from that sensory attachment, and to begin the ascent of the soul towards the world of ideas, there to participate in the divine version of reproduction, which is the understanding and the passing on of eternal truths. That is the true kind of erotic love, and is manifest in the chaste attachment between man and boy, in which the man takes the role of teacher, overcomes his lustful feelings, and sees the boy’s beauty as an object of contemplation, an instance in the here and now of the eternal idea of the beautiful. That potent collection of ideas has had a long subsequent

6.) Plato’s idea of love was adapted in medieval times as “courtly love” which involved a chaste admiration from afar.

And the heterosexual version of the Platonic myth had an enormous influence on medieval poetry and on Christian visions of women and how women should be understood, inspiring some of the most beautiful works of art in the Western tradition, from Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale and Dante’s Vita Nuova to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and the sonnets of Michelangelo.

7.) Sexual desire is inherently specific and individual, directed towards particular persons rather than interchangeable objects.

Sexual desire is determinate: there is a particular person that you want. People are not interchangeable as objects of desire, even if they are equally attractive. You can desire one person, and then another— you can even desire both at the same time. But your desire for John or Mary cannot be satisfied by Alfred or Jane: each desire is specific to its object, since it is a desire for that person as the individual that he is, and not as an instance of a general kind, even though the ‘kind’ is, at another level, what it is all about.

8.) Beauty captivates us by focusing our attention intensely on the individual object, allowing us to savor their presence fully

Beauty invites us to focus on the individual object, so as to relish his or her presence. And this focusing on the individual fills the mind and perceptions of the lover. That is why eros seemed to Plato to be so very different from the reproductive urges of animals, which have the appetitive structure of hunger and thirst. As we might put it, the urges of animals are the expression of fundamental drives, in which need, rather than choice, is in charge. Eros, on the other hand, is not a drive but a singling out, a prolonged stare from I to I which surpasses the urges from which it grows, to take its place among our rational projects.

9.) Base desire is directed at the body while higher desire is directed at the soul.

Beauty invites us to focus on the individual object, so as to relish his or her presence. And this focusing on the individual fills the mind and perceptions of the lover. That is why eros seemed to Plato to be so very different from the reproductive urges of animals, which have the appetitive structure of hunger and thirst. As we might put it, the urges of animals are the expression of fundamental drives, in which need, rather than choice, is in charge. Eros, on the other hand, is not a drive but a singling out, a prolonged stare from I to I which surpasses the urges from which it grows, to take its place among our rational projects.

10.) We must learn to love the embodied soul and not the body itself.

A body is an assemblage of body parts; an embodied person is a free being revealed in the flesh. When we speak of a beautiful human body we are referring to the beautiful embodiment of a person, and not to a body considered merely as such.

Explanation: The embodiment of a person is the holistic expression of their inner self through their physical appearance. Beauty in this context reflects the harmonious integration of physical features with the person's unique identity and presence.

11.) Obscenity is that which reduces an embodied person to a body and puts it on display for base gratification.

The obscene gesture is one that puts the body on display as pure body, so destroying the experience of embodiment. We are disgusted by obscenity for the same reason that Plato was disgusted by physical lust: it involves, so to speak, the eclipse of the soul by the body.

12. ) A beautiful soul is someone whose moral goodness is easily seen and felt by others. It's not just about doing good deeds but also about radiating virtue through their actions and thoughts.

The beautiful soul is one whose moral nature is perceivable, who is not just a moral agent but a moral presence, with the kind of virtue that shows itself to the contemplating gaze. We can feel ourselves in the presence of such a soul when we see selfless concern in action— as in the case of Mother Teresa. But we can equally feel it when sharing another’s thoughts—reading the poems of St John of the Cross, for example, or the diaries of Franz Kafka. In such cases moral appreciation and the sentiment of beauty are inextricably entwined, and both target the individuality of the person.

13.) Virginity is admired in nearly all cultures as it symbolizes an idealized form of love between individuals who embody both human and divine qualities.

It underlies the deep respect for virginity that we encounter, not only in classical and Biblical texts, but in the literatures of almost all the articulate religions arms. Mary has never been subdued by her body as others are, and stands as a symbol of an idealized love between embodied people, a love which is both human and divine. This thought reaches back to Plato’s original idea: that beauty is not just an invitation to desire, but also a call to renounce it. In the Virgin Mary, therefore, we encounter, in Christian form, the Platonic conception of human beauty as the signpost to a realm beyond desire.

14.) There are degrees of human beauty as seen in words like "pretty," "engaging," "charming," "lovely," and "attractive."

Chapter 3 - Natural Beauty

In Chapter 3 of Beauty, Roger Scruton explores the concept of natural beauty, focusing on how we perceive and value beauty in the natural world. He begins by discussing the human tendency to appreciate landscapes, plants, and animals, noting that our response to natural beauty often feels instinctive and profound.

The Philosophical Background

Scruton references the philosophical tradition, particularly the works of Immanuel Kant, who emphasized the disinterested pleasure we take in natural beauty. Kant argued that our appreciation for natural beauty is free from practical concerns and personal desires, highlighting the pure aesthetic pleasure derived from nature.

The Aesthetic Experience

Scruton elaborates on the nature of the aesthetic experience in relation to natural beauty. He explains that this experience involves a contemplative engagement with nature, where we appreciate the form, harmony, and order present in the natural world. This contemplation allows us to perceive beauty in a way that transcends mere utility or personal gain.

Beauty and the Sublime

The chapter delves into the distinction between beauty and the sublime. While beauty in nature is associated with harmony and pleasure, the sublime is linked to awe and sometimes fear. The sublime evokes a sense of grandeur and power, often seen in vast landscapes, towering mountains, and stormy seas. Scruton suggests that both beauty and the sublime contribute to our overall appreciation of nature.

The Role of Imagination

Scruton discusses the role of imagination in our perception of natural beauty. He argues that our imaginative engagement with nature allows us to see more than just the physical aspects of a landscape. Through imagination, we can perceive deeper meanings, evoke emotions, and connect with the natural world on a spiritual level.

Environmental Ethics and Aesthetic Value

The chapter also addresses the intersection of environmental ethics and the aesthetic value of nature. Scruton posits that our appreciation of natural beauty can inspire a sense of responsibility towards the environment. By recognizing the intrinsic value of natural landscapes, we are more likely to advocate for their preservation and protection.

Critique of Utilitarian Views

Scruton critiques utilitarian views that reduce the value of nature to its economic or practical benefits. He argues that such perspectives overlook the profound aesthetic and spiritual value that nature holds. By focusing solely on utility, we risk undermining the deeper connections and meanings that natural beauty provides.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Scruton reaffirms the importance of natural beauty in our lives. He emphasizes that our aesthetic appreciation of nature is a fundamental aspect of the human experience, one that enriches our understanding of the world and deepens our sense of connection to it. Natural beauty, according to Scruton, is not just a passive experience but an active engagement that shapes our ethical and spiritual perspectives.

Quotes and Principles

1.) While not everyone has developed an aesthetic taste for art and music, almsos everyone appears to have an appreciation of natural beauty.

In fact, however, appreciation of the arts is a secondary exercise of aesthetic interest. The primary exercise of judgement is in the appreciation of nature. In this we are all equally engaged, and though we may differ in our judgements, we all agree in making them. Nature, unlike art, has no history, and its beauties are available to every culture and at every time. A faculty that is directed towards natural beauty therefore has a real chance of being common to all human beings, issuing judgements with a universal force.

2.) Kant distinguished between free and dependent beauty and saw nature as being a form of free beauty.

Explanation: Free beauty, according to Kant, is inherent in natural objects and does not require us to apply concepts or judgments beforehand. It is characterized by its immediate and universal appeal, perceived without the need for prior intellectual interpretation. On the other hand, dependent beauty is found in works of art where our appreciation relies on understanding the artist's intentions and the conceptual framework behind the creation. This type of beauty is contingent upon our ability to grasp and interpret the artwork within its cultural and artistic context, making it more mediated and subjective compared to the spontaneous and universal appeal of free beauty in nature.

3.) Edmund Burke, in his treatise "On the Sublime and Beautiful" (1756), distinguishes between beauty and the sublime through contrasting emotional responses to nature:

Beauty: Burke associates beauty with feelings of love and attraction. It arises when we perceive harmony, order, and serenity in nature, evoking a sense of comfort and confirmation. Beauty makes us feel at home in the natural world, appreciating its gentle and pleasing aspects.

Sublime: In contrast, the sublime is characterized by feelings of fear and awe in response to the grandeur and power of nature. For example, standing on a vast, wind-swept mountain crag can evoke sensations of overwhelming magnitude, threatening majesty, and our own insignificance in comparison. The sublime experience confronts us with the immense and formidable aspects of nature, challenging our sense of scale and power.

Both beauty and the sublime are considered elevating experiences by Burke. They transcend the practical concerns of everyday life, offering moments of disinterested contemplation where we engage with nature's aesthetic qualities purely for their own sake.

Chapter 4: Everyday Beauty

In Chapter 4 of Beauty, Roger Scruton explores the concept of beauty in the context of everyday life. He argues that beauty is not limited to grand works of art or majestic landscapes but is also found in the ordinary aspects of our daily existence. This chapter aims to broaden the understanding of beauty by highlighting its presence in the mundane and the routine.

The Aesthetic Experience in Daily Life

Scruton begins by discussing how everyday objects and settings can possess aesthetic value. He notes that simple items, such as a well-crafted piece of furniture or a neatly arranged room, can be sources of beauty. The aesthetic appreciation of these objects arises from their form, function, and the care taken in their creation and maintenance.

The Role of Order and Harmony

A key theme in this chapter is the importance of order and harmony in creating everyday beauty. Scruton emphasizes that beauty often emerges from the arrangement and organization of elements in a coherent and pleasing manner. This can be seen in the layout of a garden, the design of a building, or the presentation of a meal. The sense of fittingness and appropriateness contributes significantly to our perception of beauty in everyday life.

The Beauty of Utility

Scruton explores the idea that utility and functionality can enhance beauty. He argues that objects designed with a clear purpose and executed with skill and precision often possess a unique aesthetic appeal. This is evident in well-designed tools, appliances, and everyday items that combine form and function seamlessly.

Beauty and the Built Environment

The chapter also addresses the aesthetic qualities of the built environment, such as streets, neighborhoods, and public spaces. Scruton argues that the design and maintenance of these spaces play a crucial role in shaping our experience of beauty in daily life. He advocates for urban planning and architecture that prioritize human scale, proportion, and harmony, creating environments that are both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

The Cultural Dimension of Everyday Beauty

Scruton acknowledges the cultural dimension of everyday beauty, noting that different cultures have unique aesthetic standards and traditions. He emphasizes that these cultural differences enrich our understanding of beauty by providing diverse perspectives on what is considered beautiful in everyday life.

The Moral and Social Aspects of Beauty

Another important aspect discussed in this chapter is the moral and social dimensions of everyday beauty. Scruton suggests that our appreciation of beauty in daily life is linked to values such as care, respect, and responsibility. The effort put into creating and maintaining beautiful environments reflects a commitment to the well-being and happiness of individuals and communities.

Critique of Modern Trends

Scruton critiques certain modern trends that he believes undermine everyday beauty. He points to the rise of utilitarianism and mass production, which often prioritize efficiency and cost over aesthetic quality. He argues that this shift has led to a decline in the appreciation and presence of beauty in everyday life, advocating for a return to values that celebrate craftsmanship, attention to detail, and aesthetic consideration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Chapter 4 of Beauty by Roger Scruton broadens the concept of beauty to include the everyday objects and environments that surround us. Scruton highlights the importance of order, harmony, utility, and cultural context in shaping our experience of everyday beauty. He argues that appreciating and fostering beauty in daily life enriches our existence and reflects our values and commitments to creating a better world.

Quotes and Principles

1.) Trends in fashion tend to be similar to the trends in architecture at the same time.

It has long been noticed, indeed, that fashions in dress and fashions in architecture have a tendency to imitate each other, and that both reflect the changing ways in which the human being and the human body are perceived.

Explanation: For instance, during periods where symmetry and classical ideals of proportion were emphasized in architecture, fashion also tended to feature structured designs and balanced silhouettes. Similarly, during times of cultural rebellion or artistic innovation, both architecture and fashion have seen shifts towards unconventional forms, materials, and aesthetics.

2.) Taste is an 18th century idea of a faculty whereby rational beings order their lives through a socially engendered sense of the right and wrong appearance.

3.) Aesthetic choices are the outward projection of our inner identity and self-determination.

Aesthetic choices form a part of what Fichte and Hegel called the Entausserung (the outward projection) of the self and the Selbstbestimmung that it generates: the self-certainty that comes through building a presence in the world of others.

4.) Fashion is a guide for aesthetic choices that will be acceptable to others in a given community.

A fashion is a guide to aesthetic choices which offers some kind of guarantee that others will endorse them. And it permits people to play with appearances, to send recognizable messages to the society of strangers, and to be at one with their own appearance in a world where appearances count. Fashion arises in the first instance by imitation. Sometimes the imitation is the result of an ‘invisible hand’—as when people imitate one another by social contagion.

5.) Aesthetic judgments can be exercising to either fit in or stand out.

Conventions create a background of unchanging order in our lives, a sense

that there is a right way and a wrong way to proceed.

Chapter 5: Artistic Beauty

In Chapter 5 of Beauty, Roger Scruton explores the realm of artistic beauty, delving into the ways art captures and expresses beauty. This chapter addresses the distinctive characteristics of beauty in art, distinguishing it from other forms of beauty found in nature or everyday life.

The Nature of Artistic Beauty

Scruton begins by defining artistic beauty, emphasizing its intentional and crafted nature. Unlike natural beauty, which exists independently of human creation, artistic beauty is a product of human intention and skill. Artists deliberately arrange elements to evoke aesthetic pleasure and convey deeper meanings, making artistic beauty a unique and complex phenomenon.

The Role of Form and Content

A central theme in this chapter is the interplay between form and content in art. Scruton argues that the beauty of an artwork arises from the harmonious relationship between its form—the arrangement of visual, auditory, or structural elements—and its content—the ideas, emotions, or narratives it conveys. This balance between form and content is crucial for achieving artistic beauty.

Aesthetic Judgment and Taste

Scruton delves into the concept of aesthetic judgment, discussing how we evaluate and appreciate artistic beauty. He suggests that aesthetic judgment is a refined and cultivated skill, developed through exposure to and engagement with art. This judgment involves both emotional response and intellectual discernment, requiring viewers to engage deeply with the artwork.

The Role of Tradition and Innovation

The chapter explores the tension between tradition and innovation in art. Scruton acknowledges the importance of artistic traditions, which provide frameworks and standards for creating and appreciating beauty. However, he also emphasizes the need for innovation, arguing that great art often arises from the creative tension between adhering to tradition and breaking new ground.

The Expression of Emotion

Artistic beauty is deeply connected to the expression of emotion. Scruton discusses how artists use various techniques to evoke and communicate emotions, creating a resonant and impactful experience for the viewer. He highlights the power of art to transcend ordinary experience, allowing individuals to connect with profound emotional and spiritual truths.

The Moral Dimension of Art

Scruton addresses the moral dimension of artistic beauty, suggesting that great art often grapples with moral and ethical questions. He argues that art has the capacity to elevate and ennoble the human spirit, providing insight into the human condition and fostering empathy and understanding. This moral aspect of art contributes to its overall beauty and significance.

Critique of Modern Art

Scruton critiques certain trends in modern art, particularly those that prioritize shock value or novelty over genuine aesthetic and moral engagement. He argues that some contemporary artworks fail to achieve true beauty because they neglect the principles of form, harmony, and meaningful content. This critique reflects Scruton's broader concern with maintaining high standards in art and aesthetics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Chapter 5 of Beauty by Roger Scruton offers a detailed examination of artistic beauty, highlighting its intentional, crafted nature and its deep connection to form, content, emotion, and morality. Scruton emphasizes the importance of aesthetic judgment, tradition, and innovation in appreciating and creating artistic beauty. This chapter underscores the transformative power of art to convey beauty and meaning, enriching human experience and understanding.

Quotes and Principles

1.) It was only in the 19th Century that art became the center of aesthetics rather than natural beauty.

Only in the course of the nineteenth century, and in the wake of Hegel’s posthumously published lectures on aesthetics, did the topic of art come to replace that of natural beauty as the core subject-matter of aesthetics. And this change was part of the great shift in educated opinion which we know as the romantic movement, and which placed the feelings of the individual, for whom self is more interesting than other and wandering more noble than belonging, at the centre of our culture.

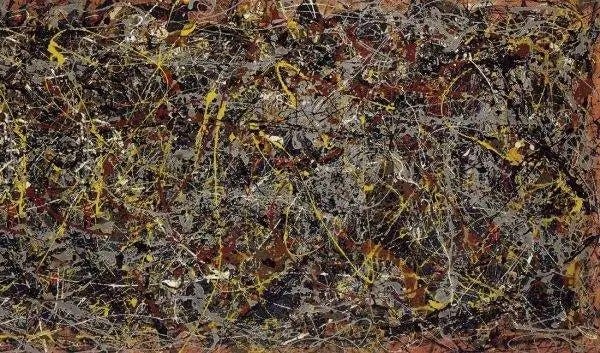

2.) Art began to decline with Marcel Duchamp’s famous urinal joke that prompted the question: what is art?

A century ago Marcel Duchamp signed a urinal with the name ‘R. Mutt’, entitled it ‘La Fontaine’, and exhibited it as a work of art. One immediate result of Duchamp’s joke was to precipitate an intellectual industry devoted to answering the question ‘What is art?’ The literature of this industry is as tedious as the never-ending imitations of Duchamp’s gesture.

3.) Aesthetic judgment is concerned with what we ought and ought not to like.

My own take: The standard for good taste ought to be what the community of the virtuous and inspired believe.

4.) The art world today is mounds of rubbish which cover the transcendent ideals we ought to aspire to.

Imagine now a world in which people showed an interest only in replica Brillo boxes, in signed urinals, in crucifixes pickled in urine, or in objects similarly lifted from the debris of life and put on display with some kind of satirical or ‘look at me’ intention—in other words, the increasingly standard fare of official modern art shows in Europe and America. What would such a world have in common with that of Duccio, Giotto, Velazquez, or even Ce´zanne? Of course, there would be the fact of putting objects on display, and the fact of our looking at them through aesthetic spectacles. But it would be a world in which human aspirations no longer find their artistic expression, in which we no longer make for ourselves images of the transcendent, and in which mounds of rubbish cover the sites of our ideals.

5.) Art is not the same thing as entertainment. Art is designed to express ideas and invites contemplation and high engagement. Entertainment is meant for temporary amusement and sensory stimulation with little engagement before or after.

The distinction was taken up by Croce’s disciple, the English philosopher R. G. Collingwood, who argued as follows. In confronting a true work of art it is not my own reactions that interest me, but the meaning and content of the work. I am being presented with experience, uniquely embodied in this particular sensory form. When seeking entertainment, however, I am not interested in the cause but in the effect. Whatever has the right effect on me is right for me, and there is no question of judgement—aesthetic or otherwise.

Purpose: Art is often created with the intention of expressing ideas, emotions, or concepts that provoke thought, reflection, or deeper understanding of the human experience. It aims to communicate something meaningful or profound, transcending mere utility or immediate pleasure. Entertainment, on the other hand, is primarily designed to amuse, engage, or provide enjoyment in the moment, often focusing on satisfying immediate desires for diversion or relaxation.

Effect: Art typically invites contemplation and interpretation, engaging the viewer or listener in a deeper exploration of its themes, symbolism, or aesthetic qualities. It may challenge norms, provoke emotions, or encourage critical thinking. Entertainment, while enjoyable, generally aims to please its audience through humor, excitement, or sensory stimulation without necessarily prompting profound reflection or enduring intellectual engagement.

Engagement: Art often demands active engagement from its audience, encouraging them to interpret and derive meaning from the work based on their own perspectives and experiences. It can inspire varied responses and interpretations over time. In contrast, entertainment tends to focus on providing immediate gratification or enjoyment, catering to popular tastes and preferences without requiring deeper intellectual or emotional involvement.

6.) Art can focus on expression or representation.

Here philosophers make a distinction between two kinds of meaning in art: representation and expression. The distinction goes back to Croce and Collingwood, though it corresponds to thoughts that have been around for far longer. It seems that works of art can be meaningful in at least two ways—by presenting a world (whether real or imaginary) that is independent of themselves, as in prose narrative, theatre or figurative painting, or by carrying their meaning intrinsically within them. The first kind of meaning is often called ‘representation’, since it implies a symbolic relation between the work and its world. Representation can be judged to be more or less realistic—in other words, more or less in conformity with the generality of the things and situations described.

Representation: This is when art shows us a world—real or imagined—that exists outside of the artwork itself. It can be a story, play, or painting that tries to depict things as they are or as they could be, like in realistic novels or detailed paintings.

Expression: This is when art focuses on expressing feelings, ideas, or the artist's unique perspective. It's less about showing the world around us and more about sharing emotions or thoughts directly through the way the artwork looks or feels.

7.) Expression is typically viewed as the more important feature of Art compared to Representation.

All those features caused Croce to dismiss representation as inessential to the aesthetic enterprise. It is at best a frame upon which artists compose, but never in itself the source of the meaning of their work. Of course, you must still understand the representational content of a work if you are to grasp its artistic meaning: and this may require critical, historical and iconographical knowledge—knowledge that is not always easy to obtain, as we know from attempts to decipher Rembrandt’s Nightwatch, or Shakespeare’s The Phoenix and the Turtle.

8.) Art gives expression to common ideas or experiences in the human condition that the viewer can sympathize with.

One suggestion is that works of art express emotion, and that this is of value to us because it acquaints us with the human condition, and arouses our sympathies for experiences that we do not otherwise undergo.

9.) Representation deals in concepts that can be translated form medium to medium but expression deals in intuitions that are entirely unique to the specific art piece.

10.) Art has meaning because of the intuitions that are expressed by it.

It seems to be saying that a work of art has meaning because of the intuition that is expressed by it.

11.) Beauty is inherently tied to being meaningful.

Art moves us because it is beautiful, and it is beautiful in part because it means something. It can be meaningful without being beautiful; but to be beautiful it must be meaningful.

12.) Hanslick and Wagner had differing views on the value of music.

Hanslick's View: Music is like building structures with sound. It focuses on the technical and structural aspects of music, seeing it as abstract and unable to directly express specific emotions. Emotions we feel from music are personal associations, not inherent in the music itself. Suggests that our emotional responses to music are subjective and personal, not necessarily intended or inherent in the music itself.

Wagner's View: Music is seen as a dramatic art that expresses and shapes our emotions. It directly communicates feelings and narratives, giving coherence to our emotional experiences. Wagner believed music could evoke deep meanings and emotional responses, making it more than just abstract patterns of sound.

13.) Art is seen to evoke emotions either through figurative associations or intuitions.

Figurative Model: Art uses figurative language (metaphors, similes, etc.) to create connections between ideas or evoke emotions in the audience. These figurative expressions aim to resonate emotionally with the perceiver.

Intuition Model: Art expresses the artist's inner, intuitive states or intuitions. It suggests that art is a way for the artist to make their inner emotional or intuitive experiences understood or felt by others.

14.) Art is a form of play that bridges reason and sensation is to impose order and meaning on human existence. The beauty of the highest art can justify the existence of life itself.

Some insight is provided by the connection made by Schiller, in his Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man, between art and play. Art, he suggests, takes us out of our everyday practical concerns, by providing us with objects, characters, scenes and actions with which we can play, and which we can enjoy for what they are, rather than for what they do for us. The artist too is playing—making imaginary worlds with the same spontaneous enjoyment that children experience, when one of them says ‘Let’s pretend!’, or producing objects that focus our emotions and enable us to understand and amend them—as Beethoven does in the late quartets In play, elevated by art to the level of free contemplation, reason and sense are reconciled, and we are granted a vision of human life in its wholeness. In appreciating art we are playing; the artist too is playing in creating it. And the result is not always beautiful, or beautiful in a predictable way. But this ludic attitude is fulfilled by beauty, and by the kind of orderliness which retains our interest and prompts us to search for the deeper significance of the sensory world.

And the impetus to impose order and meaning on human life, through the experience of something delightful, is the underlying motive of art in all its forms. Art answers the riddle of existence: it tells us why we exist by imbuing our lives with a sense of fittingness. In the highest form of beauty life becomes its own justification, redeemed from contingency.

15.) Art can turn our deep individual emotional experiences into archetypal ideas that connect us with others. It is normalizing and allows us to contemplate our deeply painful experiences with emotional distance.

We know what it is to love and be rejected, and thereafter to wander in the world infected by a bleak passivity. This experience, in all its messiness and arbitrariness, is one that most of us must undergo. But when Schubert, in Die Winterreise, explores it in song, finding exquisite melodies to illuminate one after another the many secret corners of a desolated heart, we are granted an insight of another order. Loss ceases to be an accident, and becomes instead an archetype, rendered beautiful beyond words by the music that contains it, moving under the impulse of melody and harmony to a conclusion that has a compelling artistic logic.

16.) In the 19th Century, art began to be created for its own sake rather than to teach moral principles.

During the nineteenth century there arose the movement of ‘art for art’s sake’: l’art pour l’art. The words are those of The´ophile Gautier, who believed that if art is to be valued for its own sake then it must be detached from all purposes, including those of the moral life.

17.) Art that focuses more on the message than the aesthetics becomes propoganda, especially when the message is distorted or untrue.

It is certainly a failing in a work of art that it should be more concerned to convey a message than to delight its audience. Works of propaganda, such as the socialist realist sculptures of the Soviet period or (their equivalent in prose) Mikhail Sholokhov’s Quiet Flows the Don, sacrifice aesthetic integrity to political correctness, character to caricature, and drama to sermonizing. On the other hand, part of what we object to in such works is their untruthful quality. The lessons urged upon us are neither compelled by the story nor illustrated in the exaggerated figures and characters; the propaganda message is not part of the aesthetic meaning but extraneous to it— an intrusion from the everyday world which only loses convictionwhen thrust on us in the midst of aesthetic contemplation.

18.) Art can have a moral message if it is sincere such as Bunyan’s Pilgrims Progress.

By contrast, there are works of art which contain intense moral messages in an aesthetically integrated frame. Consider John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. The advocacy of the Christian life is here embodied in schematic characters and transparent allegory. But the book is written with such immediacy and such a true feeling for the weight of words and the seriousness of sentiment, that the Christian message becomes an integral part of it, rendered beautiful by the compelling words. We encounter in Bunyan a unity of form and content that forbids us from dismissing the work as a mere exercise in propaganda.

Chapter 6: Taste and Order

In Chapter 6 of Beauty, Roger Scruton examines the concepts of taste and order, exploring how these ideas intersect with our appreciation of beauty. This chapter delves into the subjective nature of taste, the principles that guide aesthetic judgments, and the role of order in creating and perceiving beauty.

The Nature of Taste

Scruton begins by discussing the concept of taste, which he defines as the capacity to discern and appreciate beauty. Taste is inherently subjective, varying from person to person, yet it also involves a level of cultivation and refinement. Scruton emphasizes that good taste is not merely a matter of personal preference but involves a developed sense of judgment that can be educated and improved over time.

Aesthetic Experience and Judgment

The chapter explores how aesthetic experience and judgment are integral to the concept of taste. Scruton argues that appreciating beauty requires more than a passive reception; it demands active engagement and critical evaluation. Aesthetic judgments are formed through a combination of emotional response and intellectual consideration, reflecting both immediate impressions and deeper contemplation.

The Role of Order

Scruton delves into the role of order in beauty, suggesting that orderliness and harmony are fundamental to our perception of beauty. He explains that beauty often arises from the arrangement of elements in a coherent and balanced manner. This principle applies to various forms of art, from visual compositions to musical structures, where the orderly arrangement of parts creates an overall sense of beauty.

The Standards of Taste

The chapter addresses the idea of standards in taste, questioning whether there are objective criteria for judging beauty. Scruton suggests that while taste is subjective, there are still standards that can guide aesthetic judgment. These standards are informed by cultural traditions, historical contexts, and communal values, which provide a framework for evaluating beauty.

Critique of Relativism

Scruton critiques the relativistic view that all tastes are equally valid, arguing that such a perspective undermines the possibility of genuine aesthetic education and improvement. He contends that relativism fails to acknowledge the existence of better and worse judgments of beauty, which can be distinguished through critical reasoning and dialogue.

The Cultivation of Taste

The chapter discusses how taste can be cultivated through exposure to great works of art, engagement with diverse cultural expressions, and critical reflection. Scruton emphasizes the importance of education in developing good taste, advocating for an approach that balances personal exploration with the appreciation of established aesthetic standards.

The Ethical Dimension of Taste

Scruton explores the ethical dimension of taste, suggesting that our aesthetic judgments reflect broader moral and ethical values. Good taste, in this view, is not only about discerning beauty but also about recognizing and respecting the dignity and worth of the objects and individuals we encounter. This ethical perspective ties aesthetic judgment to a broader sense of responsibility and care.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Chapter 6 of Beauty by Roger Scruton offers an in-depth exploration of taste and order, highlighting their significance in the appreciation of beauty. Scruton argues that taste involves both subjective preference and cultivated judgment, guided by principles of order and harmony. He critiques relativism and emphasizes the importance of education and ethical considerations in developing good taste.

Quotes and Principles

1.) Aesthetic taste is a reflection of our moral character and thus different communities will have different aesthetic tastes.

If it is so offensive to look down on another’s taste, it is, as the democrat recognizes, because taste is intimately bound up with our personal life and moral identity. It is part of our rational nature to strive for a community of judgement, a shared conception of value, since that is what reason and the moral life require. And this desire for a reasoned consensus spills over into the sense of beauty.

2.) All private tastes will spill over into the public sphere.

This we discover as soon as we take into account the public impact of private tastes. Your neighbour fills her garden with kitsch mermaids and Disneyland gnomes, polluting the view from your window; she designs her house in a ludicrous Costa Brava style, in loud primary colours that utterly ruin the tranquil atmosphere of the street, and so on. Now her taste has ceased to be a private matter and inflicted itself on the public realm. We begin to dispute the matter: you appeal to the town council, arguing that her house and garden are not in keeping with the street, that this particular part of town is scheduled to retain a Georgian serenity, that her house clashes with the classical facades of adjacent buildings. (In a recent British case a house-owner, influenced by art-school fashions, erected a plastic sculpture of a shark on his roof, to give the appearance of a great fish that had crashed through the tiles into the attic. Protests from neighbours and the local planning officer led to a prolonged legal battle, which the house-owner—an American, who no longer lives in the house—eventually won.)

3.) Planning laws are aimed at preserving the aesthetic taste of a community.

Implicit in our sense of beauty is the thought of community—of the agreement in judgements that makes social life possible and worthwhile. That is one of the reasons why we have planning laws—which, in the great days of Western civilization, have been extremely strict, controlling the heights of buildings (nineteenth-century Helsinki), the materials to be used in construction (eighteenth-century Paris), the tiles to be used in roofing (twentieth-century Provence), even the crenelations on buildings that face the thoroughfares (Venice, from the fifteenth century onwards).

4.) Plato believed that music was tied to morality and that only music which was conducive to morality should be permitted.

Plato believed that the various modes of music are connected with specific moral characteristics of those who dance or march to them, and that in a well-ordered city only those modes would be permitted which are in some way fitted to the virtuous soul.

5.) Taste is significantly influenced by what we have been exposed to repeatedly.

You like Brahms, say, and I detest him. So you invite me to listen to your favourite pieces, and after a while they ‘work on me’. Maybe I am influenced by my friendship for you, and make a special effort on your behalf. How it happens, I do not know—but if it happens, that I come to like Brahms, then this is not a rational decision, nor a rational conclusion of mine: it is a change comparable to that undergone by children when, having begun life by hating greens, they learn at last to relish them. An experience that repelled them now attracts them; but it was not an argument that persuaded them. A change of taste is not a ‘change of mind’, in the way that a change of belief or even of moral posture is a change of mind. This doesn’t mean that there are no extraneous reasons that might justify the change in taste.

How Taste Develops

Initial Exposure: Taste begins to form when we are exposed to different forms of art, music, literature, etc., either through personal exploration or cultural influences.

Repetition and Familiarity: Continued exposure to these forms leads to familiarity, allowing us to recognize patterns, styles, and elements that we enjoy or find appealing.

Emotional Response: As we engage with different works, we develop emotional responses—liking what resonates emotionally or intellectually with us.

Comparison and Contrast: Through exposure to various works, we start comparing and contrasting them based on our emotional and aesthetic responses, refining what we perceive as good or enjoyable.

Personal Reflection: Over time, we reflect on our preferences, considering what aspects of art or culture align with our values, experiences, and worldview.

Social and Cultural Influence: Interactions with peers, mentors, or cultural norms further shape our tastes by validating certain preferences or introducing new perspectives.

Continual Exploration: Taste evolves through ongoing exploration and openness to new experiences, which may challenge or reinforce existing preferences.

6.) David Hume saw beauty as a reflection of the observer rather than an intrinstic quality of an object itself.

To establish a standard of taste, Hume suggested identifying individuals with refined sensibilities and good judgment. These individuals serve as reliable guides whose tastes and discriminations can be trusted to reflect broader standards of beauty.

Subjective Sentiment: According to Hume, the standard of taste does not reside in the inherent qualities of the object being judged but rather in the subjective sentiments and preferences of the judge. The judgment of beauty is thus grounded in the emotional and aesthetic response of the observer.

7.) Hume believed we could find reliable and informed guides for determining what is beautiful and that beauty standards ought to be maintained.

In a celebrated essay Hume tried to shift the focus of the discussion, arguing roughly as follows: taste is a form of preference, and this preference is the premise, not the conclusion of the judgement of beauty. To fix the standard, therefore, we must discover the reliable judge, the one whose taste and discriminations are the best guide.

8.) We should find virtuous and educated judges to establish a standard of taste for the masses of people to emulate.

Chapter 7: Art and Eros

In Chapter 7 of Beauty, Roger Scruton delves into the intricate relationship between art and eros, examining how erotic themes and elements of desire have been represented in art throughout history. He explores the ways in which art captures and conveys erotic beauty, and the philosophical implications of such representations.

The Erotic in Art

Scruton begins by discussing the role of the erotic in art, noting that erotic themes have been a significant subject in various art forms, including painting, sculpture, literature, and music. He explains that erotic art goes beyond mere depiction of physical beauty or sexual desire; it seeks to evoke a deeper emotional and psychological response, engaging the viewer's imagination and sensibilities.

Representation and Expression

The chapter explores how artists represent and express erotic themes. Scruton emphasizes that successful erotic art does not merely titillate but elevates and transforms the experience of desire. It captures the complexities of human relationships, the subtleties of attraction, and the profound connection between lovers. This transformation of desire into an aesthetic experience is a key aspect of the beauty found in erotic art.

The Moral and Aesthetic Dimensions

Scruton delves into the moral and aesthetic dimensions of erotic art. He argues that while erotic art can enhance our appreciation of beauty and deepen our understanding of human relationships, it also raises ethical questions. The representation of erotic themes must be handled with sensitivity and respect to avoid objectification and exploitation. Scruton discusses the fine line between celebrating erotic beauty and descending into vulgarity or pornography.

Historical Perspectives

The chapter provides a historical overview of how different cultures and artistic traditions have approached erotic themes. Scruton examines examples from classical antiquity, the Renaissance, and modern art, highlighting how changing cultural norms and values have influenced the portrayal of eros in art. He notes that while some periods embraced erotic art openly, others were more restrained or even repressive.

The Role of the Viewer

Scruton explores the role of the viewer in engaging with erotic art. He suggests that the viewer's response to erotic art is shaped by personal experiences, cultural background, and moral framework. The appreciation of erotic beauty requires a balance of emotional openness and critical discernment, allowing the viewer to engage with the artwork on multiple levels.

The Transformative Power of Eros

The chapter discusses the transformative power of eros in art, suggesting that erotic beauty can lead to a deeper understanding of the self and others. Scruton argues that the contemplation of erotic art can be a profoundly enriching experience, fostering empathy, emotional growth, and a greater appreciation of the complexities of human love and desire.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Chapter 7 of Beauty by Roger Scruton provides a comprehensive exploration of the relationship between art and eros. Scruton examines how erotic themes are represented in art, the moral and aesthetic considerations involved, and the transformative potential of erotic beauty. He emphasizes that erotic art, when done well, elevates and enriches our experience of beauty, deepening our understanding of human desire and connection.

Quotes and Principles

1.) The nude in true art is not naked but is unclothed and shows the human body in normal poses as if they were wearing clothing.

Anne Hollander has written of the extent to which the nude, in our tradition, is not naked but unclothed: it is a body marked by the shapes and materials of its normal covering. In Titian the body is at rest just as it would be if it were protected from our gaze by a veil of clothing: it is a body under invisible clothes. We no more detach it from the face or the personality than we would detach the body of a woman fully dressed. And by painting the body in this way Titian overcomes its eerie quality—its nature as forbidden fruit. This effect would vanish were the face to be replaced by an off-the-shelf stereotype of the kind used by Boucher. In Boucher the face is a pointer to the body, which is its raison d’eˆtre.

2.) The Birth of Venus is an example of erotic art that is not pornographic as Venus is not portrayed to excite desire.

Anne Hollander has written of the extent to which the nude, in our tradition, is not naked but unclothed: it is a body marked by the shapes and materials of its normal covering. In Titian the body is at rest just as it would be if it were protected from our gaze by a veil of clothing: it is a body under invisible clothes. We no more detach it from the face or the personality than we would detach the body of a woman fully dressed. And by painting the body in this way Titian overcomes its eerie quality—its nature as forbidden fruit. This effect would vanish were the face to be replaced by an off-the-shelf stereotype of the kind used by Boucher. In Boucher the face is a pointer to the body, which is its raison d’eˆtre.

3.) Pornography focuses on the body as an object while erotic art focuses on the embodied person.

In distinguishing the erotic and the pornographic we are really distinguishing two kinds of interest: interest in the embodied person and interest in the body—and, in the sense that I intend, these interests are incompatible. (See the discussion in Chapter 2.) Normal desire is an inter-personal emotion. Its aim is a free and mutual surrender, which is also a uniting of two individuals, of you and me—through our bodies, certainly, but not merely as our bodies. Normal desire is a person to person response, one that seeks the selfhood that it gives. Objects can be substituted for each other, subjects not. Subjects, as Kant persuasively argued, are free individuals; their non-substitutability belongs to what they essentially are. Pornography, like slavery, is a denial of the human subject, a way of negating the moral demand that free beings must treat each other as ends in themselves.

4.) The purpose of pornography is to arouse desire in the observer while erotic art is to portray the sexual desire of those in the painting.

The purpose of pornography is to arouse vicarious desire; the purpose of erotic art is to portray the sexual desire of the people pictured within it—and if it also arouses the viewer, as Correggio does from time to time, then this is an aesthetic defect, a ‘fall’ into another kind of interest than that which has beauty as its target. Hence erotic art veils its subject matter, in order that desire should not be traduced and expropriated by the observer. The supreme achievement of erotic art is to cause the body to veil itself—to make the flesh itself into an expression of the decency that forbids the voyeur, so that the subjectivity of the nude is revealed even in those parts of the body that are outside the province of the will.

5.) Boucher’s Blonde Odalisque is an example of art that turns pornographic as the model is in an unnatural pose that would only occur during sex.

Turn now to Boucher’s Blonde Odalisque, and you will see how very different is the artistic intention. This woman has adopted a pose that she could never adopt when dressed. It is a pose which has little or no place in ordinary life outside the sexual act, and it draws attention to itself, since the woman is looking vacantly away and seems to have no other interest. But there is another way in which Boucher’s painting touches against the bounds of decency, and this is in the complete absence of any reason for the Odalisque’s pose within the picture. She is alone in the picture, looking at nothing in particular, engaged in no other act than the one we see. The place of the lover is absent and waiting to be filled: and you are invited to fill it.

6.) Pornography desecrates the beauty of those involved as it turns subjects into objects and people into things.

The discussion of Titian’s Venus indicates, I think, why pornography lies outside the realm of art, why it is incapable of beauty in itself and desecrates the beauty of the people displayed in it. The pornographic image is like a magic wand that turns subjects into objects, people into things—and thereby disenchants them, destroying the source of their beauty. It causes people to hide behind their bodies, like puppets worked by hidden strings.

7.) The body is not an object but is an incarnation and inextricably linked with the self. To prostitute the body is to prostitute the soul.

On this view my body is not my property but—to use the theological term—my incarnation. My body is not an object but a subject, just as I am. I don’t own it, any more than I own myself. I am inextricably mingled with it, and what is done to my body is done to me. And there are ways of treating it that cause me to think and feel as I would not otherwise think or feel, to lose my moral sense, to become hardened or indifferent to others, to cease to make judgements or to be guided by principles and ideals. When this happens it is not just I who am harmed: all those who love me, need me or relate to me are harmed as well. For I have damaged the part on which relationships are built.

The condemnation of prostitution was not just puritan bigotry; it was a recognition of a profound truth, which is that you and your body are not two things but one, and by selling the body you harden the soul. And that which is true of prostitution is true of pornography too. It is not a tribute to human beauty but a desecration of it.

8.) The case against pornography is simply the case against seeing and treating people as objectified animals and reduced to their bodies.

Moreover human beauty belongs to our embodiment, and art that ‘objectifies’ the body, removing it from the realm of moral relations, can never capture the true beauty of the human form. By desecrating the beauty of people, it desecrates itself. The comparison between pornography and erotic art shows us that taste is rooted in our wider preferences, and that these preferences express and encourage aspects of our own moral character. The case against pornography is the case against the interest that it serves—the interest in seeing people reduced to their bodies, objectified as animals, made thing-like and obscene.

Chapter 8: The Flight from Beauty

In Chapter 8 of Beauty, Roger Scruton examines the modern tendency to reject or devalue beauty in art and culture. He explores the philosophical, cultural, and social factors that have contributed to this trend and critiques the implications of this shift away from beauty.

The Historical Context

Scruton begins by situating the flight from beauty within a historical context. He notes that in previous centuries, beauty was a central concern of artists, philosophers, and the public. Beauty was seen as a noble pursuit, integral to the creation and appreciation of art. However, in the modern era, there has been a marked departure from this focus.

The Influence of Modernism