1.) Young Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte, an iconic figure from history, is often envisioned as a remarkable military leader mounted on a white horse, self-crowning as an emperor, and famously posed with his hand inside his jacket. Let's delve into the less celebrated aspects of his life, focusing on his younger years, both as a military strategist and a politician, and revealing a side not widely known: his romantic and sentimental nature.

Born in 1769 on the island of Corsica, which primarily spoke Italian, Napoleon was initially named Napoleone Buonaparte. He later anglicized his name in the mid-1790s as he embraced French identity. His family belonged to the minor nobility. His father, Carlo Buonaparte, a lawyer and ambitious social climber, engaged in various business ventures but died young and in debt. Napoleon's mother, Letizia, was a force to be reckoned with—energetic, spirited, and demanding, traits she instilled in her son. Napoleon shared a close bond with his elder brother, Joseph, who was more reserved compared to the vivacious future emperor.

For education, noble Corsican families often sent their sons to France; thus, Napoleon, alongside Joseph, went to France where Joseph pursued religious studies and Napoleon entered a military academy. The young Bonaparte struggled at the Brienne military academy due to its rigorous conditions and because he was an outsider who spoke French with a heavy accent. Nevertheless, he excelled in mathematics and showed great interest in history and geography. His education continued at the elite military academy in Paris, and upon graduating, he joined the artillery as an officer.

Politically, Napoleon's early experiences in Corsica deeply influenced him. The island had been seized by the French just months before his birth, quashing its independence movement, a cause his father had supported. Growing up, Napoleon was imbued with tales of Corsican valor and developed a keen interest in the politics of his homeland. Despite his initial political engagements in Corsica, his naive approach and underestimation of resistance led to a sharp political and personal defeat by Pasquale Paoli, a prominent Corsican leader. This setback played a crucial role in shaping his identity; he lost his Corsican nationalist aspirations but never fully integrated into French society, remaining somewhat of an outsider—a status that fueled his relentless self-reinvention.

The French Revolution opened new opportunities for Napoleon. During the Revolution, he aligned himself with the Jacobins and Robespierre, drawn by the revolutionary fervor and its glorification of military prowess. The revolution's chaotic environment, particularly the radical shifts it brought to military and political structures, allowed him to ascend rapidly in rank based on merit. His military acumen was notably demonstrated during the Siege of Toulon against the British, where his strategic use of artillery was crucial to the French victory. This success earned him a promotion and solidified his reputation.

Amidst his military and political rise, Napoleon also lived through a period that encouraged the open expression of emotion, a stark contrast to his later perceived ruthlessness. He immersed himself in the romantic and intellectual currents of the time, even beginning a novel. His personal life became intertwined with the influential Josephine de Beauharnais, a widow six years his senior, whom he passionately pursued and eventually married. However, their marriage was marked by tumult, as Josephine was not as captivated by him and soon engaged in an affair.

Napoleon's impact extended beyond France. The revolutionary wars allowed France to exert influence over its neighbors, notably seen in the establishment of the Batavian Republic in the Netherlands. This move demonstrated France's tendency to blend revolutionary ideals with traditional power politics, exploiting the republics it helped create for financial gain and strategic advantage.

In summary, Napoleon's early years were marked by a complex blend of personal ambition, romantic sentimentality, and ruthless pragmatism, set against the backdrop of revolutionary upheaval and the shifting sands of European politics. His journey from a young Corsican outsider to a dominant French figure is a testament to his dynamic adaptability and relentless pursuit of power.

2.) The Italian Campaign

In the spring of 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte dramatically shifted the political and military landscape of Italy. Within just six weeks of taking command, he led his troops into Milan, displacing its Austrian rulers and igniting a wave of revolutionary zeal throughout northern Italy. His arrival was celebrated by locals and intellectuals alike, with a Venetian playwright famously expressing admiration for Bonaparte's multifaceted leadership.

Before Bonaparte's arrival, Italy was fragmented into various states with diverse governments, from monarchies in Piedmont and Naples to the independent Venetian Republic and the Austrian-dominated Duchy of Milan. The French Revolution had already stirred excitement and revolutionary ideas among Italians, challenging local authorities who struggled to suppress these sentiments.

Despite initial hesitations from the French Directory, which was focused on consolidating territories closer to France, Bonaparte saw an opportunity in Italy. The French were at war with Britain, Austria, and several Italian states, and while other French armies faced setbacks, Bonaparte’s campaign in Italy was swift and decisive. He began by quickly subduing Piedmont and, by mid-May, entered Milan to enthusiastic acclaim.

Bonaparte's military strategy in Italy showcased his innovative approach to warfare. With a relatively small and underequipped army, he emphasized rapid movements and logistical efficiency, often relying on local resources rather than traditional supply lines. His tactics included the “mixed order” system, which allowed for flexible and dynamic combat formations, proving effective in outmaneuvering his adversaries.

One of the pivotal moments of this campaign was the Battle of Lodi, where Bonaparte led a daring charge across the Adda River, overcoming strong Austrian defenses and solidifying his reputation as a fearless leader. This victory was not just a military triumph but also a symbol of Bonaparte’s growing influence, which he adeptly used to boost his image through propaganda.

As Bonaparte advanced through Italy, he not only pushed Austrian forces back but also began to lay the groundwork for the creation of sister republics, aligned with revolutionary France. Despite the Directory's initial reluctance, Bonaparte supported Italian patriots in overthrowing local rulers and establishing new republics, such as the Cisalpine Republic in Milan. He carefully managed these political transformations, aiming to maintain moderate governments that could stabilize these new states.

However, the political landscape was complex, and Bonaparte's agreements, particularly the Treaty of Campo Formio, in which he traded Venice for Austrian recognition of the Italian republics, sparked controversy and disillusionment among Italian revolutionaries. This decision highlighted a shift in French revolutionary policy—from spreading ideological principles to pursuing pragmatic geopolitical interests.

Bonaparte’s Italian campaign not only reshaped Italy but also significantly altered his own position in France. His military successes and the strategic establishment of client states bolstered his status and influence, marking him as a formidable force in both military and political arenas. This period was crucial in defining Bonaparte's legacy as a master strategist and a shaper of nations, setting the stage for his future ascendancy in European history.

3.) France and America

In the late 1790s, while France was establishing sister republics throughout Europe, its relationship with its ideological counterpart across the Atlantic, the United States, began to deteriorate. Initially united by revolutionary fervor, the two nations found their alliance tested as their political and geopolitical interests increasingly clashed.

At the onset of the French Revolution, the United States and France shared a mutual admiration, inspired in part by the Americans' recent overthrow of British rule. The French Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789 drew from American democratic principles. However, as the French Revolution intensified, becoming far more radical than the American Revolution, American enthusiasm began to wane. Key differences in their revolutions—such as the American absence of a monarch and a powerful church—led figures like Robespierre to dismiss the American example as irrelevant to France's complex social upheaval.

In America, the French Revolution deepened political divisions, giving rise to the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties. Federalists, led by figures like John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, sought a strong central government and closer ties with Britain, viewing the French push for equality with skepticism. Conversely, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, admired France and advocated for greater democratic participation and state power.

The arrival of French diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt in 1793 marked a pivotal moment in Franco-American relations. Sent by the Girondins, Genêt's mission was to secure American repayment of debts from the Revolutionary War and to strengthen the Franco-American alliance against Britain and Spain. However, his aggressive tactics, including plans to incite insurrections in Spanish and British territories in North America, alarmed the U.S. government. President Washington's proclamation of neutrality in the conflict between Britain and France, and Genêt's subsequent actions, which included outfitting privateers and threatening to bypass Washington by appealing directly to the American people, ultimately led to his diplomatic failure.

The fallout from Genêt's mission exacerbated tensions between the U.S. and France. The Jay Treaty of 1794, which aligned the U.S. more closely with Britain, was seen by the French as a betrayal. Relations deteriorated further during the XYZ Affair in 1797, when French demands for bribes from American diplomats ignited public outrage in the U.S. and led to the undeclared Quasi-War between the two nations.

This period of conflict empowered the Federalists to implement the Alien and Sedition Acts, targeting immigrants and suppressing Republican dissent. However, these measures proved unpopular and contributed to the Democratic-Republicans' victory in the 1800 election, leading to a reassessment of U.S. foreign policy and a subsequent peace agreement with France.

The Franco-American relationship in the 1790s illustrates the complex interplay between ideological affinity and realpolitik. While both nations initially celebrated their shared republican ideals, their differing national interests and internal political pressures led to a reevaluation of their alliance. This period highlighted the challenges of navigating international relations in a time of revolutionary change, leaving a lasting impact on the diplomatic strategies of both nations.

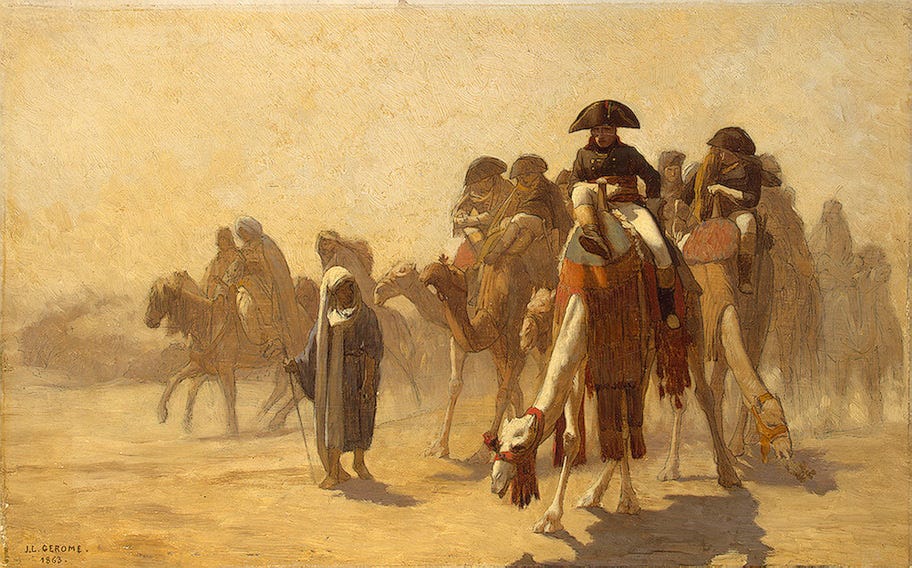

4.) Napoleon in Egypt

In the winter of 1797-1798, after a victorious campaign in Italy, Napoleon Bonaparte returned to Paris. His military prowess was unmatched, but his next assignment was mundane: to assess the feasibility of invading England. Napoleon, however, had other ambitions. He proposed a bold plan to undermine British power by seizing Egypt, which he envisioned as a new French colony and a strategic point to disrupt British trade routes to India.

By May 1798, Napoleon embarked on this Egyptian venture with a massive fleet and thousands of soldiers and specialists. This move was quietly welcomed by the French government, who viewed the politically ambitious Napoleon as a potential threat at home.

France had long been interested in Egypt, a sentiment that was revitalized by Foreign Minister Talleyrand in the late 1790s. Egypt, part of the Ottoman Empire but effectively governed by the Mamluk dynasty, was seen as a weak point in the Ottoman control and a lucrative opportunity for establishing a sugar-producing colony. Moreover, Egypt's strategic location offered the potential to challenge British influence in India and promote French trade.

The French expedition was not just a military campaign but also a scientific and cultural mission. Napoleon brought along scientists, engineers, and artists to study and document Egypt's ancient civilization. This endeavor highlighted the romantic allure of Egypt, which Europeans considered the cradle of civilization.

Upon reaching Alexandria, Napoleon issued a proclamation promising liberation from Mamluk tyranny, though his message failed to win the hearts of the Egyptian elites. His troops marched to Cairo, facing harsh conditions and resistance from local forces. At the Battle of the Pyramids, Napoleon employed tactical formations that repelled the formidable Mamluk cavalry, leading to the capture of Cairo.

However, the campaign faced a significant setback at the Battle of the Nile in Aboukir Bay, where a British fleet led by Admiral Nelson destroyed the French Mediterranean fleet. This naval defeat isolated Napoleon's forces in Egypt, preventing any reinforcements or easy retreat.

Despite this, Napoleon initiated a series of reforms in the Nile Delta, attempting to modernize Egypt through infrastructure projects and the establishment of new administrative systems. He tried to integrate local leaders into his government and assured the Muslim population that their religion was respected. Nonetheless, these efforts were met with mixed reactions, and a revolt in Cairo challenged his rule.

Napoleon's ambitions extended beyond Egypt. In 1799, he led a campaign into Syria to preempt an Ottoman counterattack. The siege of Acre, however, was a failure, marked by stiff resistance and logistical difficulties. Returning to Egypt, Napoleon found his position untenable and, learning of political instability in France, he abandoned his army and returned to France, leaving his generals in charge.

Napoleon's Egyptian adventure, while a military and logistical failure, paradoxically enhanced his reputation in France. He was celebrated for his daring and vision, even though his grandiose plans for Egypt did not materialize. The campaign left a lasting impact on Egypt and Europe, igniting a wave of Egyptomania and influencing the development of Egyptology. For Napoleon, Egypt was a land of dreams and ambitions, a chapter of his life filled with grandeur and idealism, despite its ultimate futility in practical terms.

5.) Napoleon Seizes Power

In 1799, amidst a backdrop of political instability and dissatisfaction with the ruling Directory, Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in a dramatic coup d'état. The Directory, which had governed France since 1795, struggled with issues like divisive religious policies, unpopular conscription rounds, and a failure to unify the republic after the turbulent Terror period. Its attempts to maintain control by overturning election results only further eroded its legitimacy and support among the French populace.

Abbé Sieyès, a prominent political figure who had risen to fame with his pamphlet "What Is the Third Estate?" in 1789, was among the directors dissatisfied with the existing government. He saw in Napoleon, fresh from his Egyptian campaign, the ideal leader to help establish a more stable and authoritarian regime. The two men, though different in temperament and background, shared the objective of dismantling the Directory.

The coup, known as the Coup of 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799), was initially planned and executed with precision. Sieyès and his allies in the legislature fabricated a crisis by alleging a fictitious neo-Jacobin plot, which they used to justify relocating the legislative bodies out of Paris to the Château of Saint-Cloud, ostensibly to protect the legislators but realistically to isolate them from the city's volatile political influence.

However, the execution of the coup at Saint-Cloud was not smooth. When confronted by the legislators, Napoleon, who was usually articulate and commanding, became flustered. It was his brother Lucien, then president of the Council of Five Hundred, who managed to salvage the situation. Lucien portrayed Napoleon as the protector of French liberty, not its usurper, and rallied the troops to disperse the resistant legislators. This military intervention effectively ended the Directory and set the stage for the establishment of the Consulate.

In the aftermath, a provisional government was set up with Napoleon as one of the three consuls, though he was the clear leader. The new government moved quickly to draft the Constitution of the Year VIII, which significantly restructured the French government, concentrating power in the hands of the executive, specifically the First Consul—Napoleon himself. This constitution eliminated the direct electoral system in favor of a complex structure where legislative bodies had limited power and were largely controlled by the executive.

The transition from the Directory to the Consulate was marked by a desire for stability and strong leadership, which Napoleon provided. He reversed unpopular measures of the Directory and sought to reassure various factions within France that his regime would not return to the extremes of the Terror. His swift and decisive actions, coupled with his charismatic leadership, helped consolidate his power and usher in a period of relative stability and reform, which eventually led to his proclamation as Emperor in 1804.

Napoleon's rise to power reflected the complexities of the French Revolution's legacy—balancing revolutionary ideals with the pragmatic need for order and leadership. His statement, "I am the Revolution. The Revolution is over," encapsulates this duality, positioning him as both a revolutionary leader and a stabilizing force, bringing an end to a decade of upheaval.

6.) General and First Consul

From 1799 to 1804, France was governed by the Consulate with Napoleon Bonaparte at its helm as the First Consul. This period marked a critical phase in Napoleon's consolidation of power, where he skillfully navigated between revolutionary ideals and conservative reassurances, ultimately steering France towards a centralized authoritarian regime under his control.

1. Military Triumphs and Political Strategy

Battle of Marengo (1800): Shortly after seizing power, Napoleon faced a precarious international situation with France on the brink of losing its grip over Italy and continuous threats from Britain and Austria. In a daring move, Napoleon led a strategic offensive across the Alps and directly into northern Italy, culminating in the Battle of Marengo. Despite initial setbacks and heavy losses, including the death of General Desaix, French forces achieved a dramatic come-from-behind victory that forced the Austrian General Mélas to retreat and sign an armistice. This victory was crucial not only for regaining territory but also for bolstering Napoleon’s image as a military genius and a stabilizing force in France.

2. Diplomatic Successes

Following his military successes, Napoleon proved adept at diplomacy, securing peace with most of Europe's major powers through the Treaties of Lunéville (1801) with Austria and Amiens (1802) with Britain. These treaties recognized French dominance over much of Western Europe and were critical in establishing a temporary peace in Europe, enhancing Napoleon's reputation as a peacemaker.

3. Political Reforms and Centralization of Power

In domestic politics, Napoleon focused on depoliticizing France by restricting political clubs, censoring the press, and purging the Tribunate of opposition. He moved into the Tuileries Palace, presenting himself as a simple, dedicated servant of the Republic, yet his actions increasingly centralized power in his own hands. He implemented a new constitution that significantly limited the power of the legislative bodies and enhanced the executive authority of the Consuls, particularly himself as the First Consul.

4. Handling of Opposition and the Christmas Eve Plot

Despite his efforts to stabilize France, Napoleon faced various plots and resistance. The most notable was the Christmas Eve plot of 1800, where he narrowly escaped an assassination attempt. He used this incident to crack down on perceived Jacobin and Royalist threats, executing and deporting many without fair trials, demonstrating his willingness to use repressive measures to maintain control.

5. Concordat of 1801

Recognizing the ongoing religious strife as a source of discord, Napoleon negotiated the Concordat of 1801 with Pope Pius VII. This agreement resolved many of the religious conflicts stemming from the Revolution by acknowledging Catholicism as the majority religion in France while maintaining state control over church properties. This move was widely popular and helped consolidate support from previously alienated segments of the population.

6. Election as First Consul for Life

By August 1802, Napoleon's consolidation of power was near complete when he was elected First Consul for life following a plebiscite. This marked a significant turning point towards authoritarian rule, as it effectively ended the Revolution's experiment with representative democracy and set the stage for his eventual proclamation as Emperor in 1804.

Napoleon's early years as First Consul illustrate how he combined military prowess with strategic political maneuvers to transform the unstable French Republic into a centralized authoritarian regime under his control. His ability to appeal to both revolutionary and traditional values, manage opposition, and negotiate peace treaties played pivotal roles in his rise to absolute power.

7.) Napoleon as Emperor

By 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte's transformation from First Consul to a monarch-like figure was well underway, leading to his proclamation as Emperor in 1804. The question of why the French, having fought so fervently for a republic during the Revolution, were willing to accept such a dramatic shift in governance is multi-faceted, involving Napoleon's personal evolution, his strategic use of familial relationships, and significant political maneuvers.

Napoleon’s Personal and Familial Dynamics

Josephine’s Influence: In the early 1800s, Napoleon reconciled with his wife Josephine, despite her previous infidelities, showcasing a private capacity for forgiveness and stability that endeared him to the public. Josephine’s charm and political acumen became central to the new court, enhancing its appeal and legitimacy.

Family Promotions: Napoleon strategically placed his siblings in positions of influence, mirroring traditional monarchical practices of consolidating power within the family. This not only secured his regime but also prepared a line of succession that might ensure long-term stability.

Political and Military Maneuvers

Execution of the Duke d’Enghien: In 1804, the controversial execution of the Duke d’Enghien marked a turning point. This act was internationally condemned but domestically, it reinforced Napoleon’s image as a decisive leader willing to take extreme measures to protect his regime from both external and internal threats.

Establishment of the Empire: Following the Duke's execution, debates within Napoleon’s government quickly led to the establishment of the Empire. The decision was framed as a necessary evolution to protect the leader and the nation, appealing to the public’s desire for stability and continued revolutionary achievements under a strong, singular leader.

Public Perception and Institutional Changes

Coronation and Its Symbolism: Napoleon’s coronation in 1804 was a blend of religious traditionalism and revolutionary symbolism, implying a divine endorsement of his rule. By involving Pope Pius VII, Napoleon sought to reconcile with the Church and by extension, with the broader French populace still attached to their Catholic roots.

Legal and Social Reforms: The Napoleonic Code, instituted in 1804, encapsulated this blend of revolutionary ideals with authoritarian control. It preserved revolutionary principles like the abolition of feudalism and equality before the law but emphasized strong central authority over the chaos of revolutionary freedom.

Conclusion: Acceptance of Napoleon’s Rule

The French acceptance of Napoleon as Emperor, replacing the tumultuous decade of republican experimentation, stemmed from a combination of weariness with ongoing political instability, admiration for Napoleon’s successes, and the promise of stability and order he represented. Napoleon’s ability to present himself as the embodiment of the Revolution’s successes—while simultaneously curtailing its excesses and stabilizing the nation—convinced many French citizens that his rule could be the harbinger of a new era of French greatness, balancing legacy with reform.

8.) Napoleon’s Ambitions in the New World

Napoleon Bonaparte’s aspirations extended far beyond the European continent. His colonial ambitions in the Atlantic world, particularly in Louisiana and Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), were part of a larger strategy to establish a French empire that could rival Britain's global dominance. This strategy was influenced by both economic motivations and geopolitical rivalries.

Louisiana Territory

Strategic Importance: Louisiana held significant value for Napoleon due to its potential to support the sugar colonies in the Caribbean through the provision of essential resources like timber and food. Controlling the port of New Orleans was crucial as it allowed for the easy transport of goods down the Mississippi River, making the territory a linchpin in Napoleon’s vision for a western empire.

Acquisition and Loss: The secret treaty with Spain in 1800 allowed France to regain control of Louisiana. However, the subsequent transfer of the territory to the United States in 1803 through the Louisiana Purchase was prompted by practical considerations. Napoleon needed funds for impending conflicts in Europe and realized that maintaining and defending the vast, underdeveloped territory would be overly burdensome.

Saint-Domingue

Economic Recovery and Autonomy: Under the leadership of Toussaint Louverture, Saint-Domingue was recovering economically by reinstating the plantation system, albeit under a new model that banned slavery and promoted racial equality. Toussaint’s constitution of 1801, which made him governor for life, was a direct challenge to French colonial authority, asserting a semi-independent governance structure.

Napoleon’s Response and Failure: Napoleon’s attempt to reassert control over Saint-Domingue and restore slavery was motivated by economic pressures from plantation owners in France. The resulting armed conflict devastated the French forces, mainly due to fierce resistance from the local population and the outbreak of yellow fever.

Impact and Consequences

End of Napoleon’s Atlantic Ambitions: The failure to subdue Saint-Domingue and the sale of Louisiana marked the end of Napoleon’s plans for a French empire in the Americas. These events shifted his focus back to Europe and contributed to his decision to crown himself Emperor in 1804, a move that solidified his control but also signaled a retreat from overseas expansionist policies.

Global Implications: The relinquishment of Louisiana to the United States doubled the size of the young nation and paved the way for westward expansion, which had profound long-term effects on Native American populations and the spread of slavery. In Haiti, the successful slave rebellion led to the establishment of the second independent republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first to abolish slavery entirely.

Renewed Conflict with Britain: The breakdown of the Treaty of Amiens and the resumption of hostilities with Britain in 1803 were partly fueled by Napoleon’s aggressive policies. The ongoing conflict with Britain would dominate Napoleon’s foreign policy until his eventual defeat.

Napoleon’s actions in the Atlantic reflect a complex interplay of ambition, economic interests, and geopolitical strategy. While he achieved temporary successes, the lasting legacy of these endeavors was a reshaped Atlantic world where colonial ambitions led to new national identities and global power shifts.

9.) Taking on the Great Powers

François-René de Chateaubriand's vivid description of Napoleon Bonaparte as one who "threw himself upon the world and shook it" aptly captures the essence of Napoleon's transformative impact on Europe, particularly during the pivotal year of 1805. This was a period when Napoleon's Grande Armée demonstrated its formidable strength, decisively altering the political landscape of Europe through the Danube campaign and the Battle of Austerlitz.

Return to War and the Formation of the Third Coalition

European Alarm: Napoleon's aggressive foreign policy, his self-coronation as Emperor, and his reorganization of territories within the Holy Roman Empire alarmed other European powers. His unilateral actions, such as the annexation of Genoa and the declaration of the Kingdom of Italy, pushed Austria to its breaking point, prompting the formation of the Third Coalition with Britain, Russia, and Sweden.

Motivations for War: The coalition was motivated by a combination of geopolitical strategy and personal animosities. Czar Alexander I of Russia, in particular, saw Napoleon not just as a political rival but as a direct threat to his own imperial ambitions in Eastern Europe.

The Grande Armée

Revolutionary Military Tactics: Napoleon’s Grande Armée was an innovative military force, combining seasoned officers from the Old Regime with conscripts and volunteers from the revolutionary era. This blend of experience and revolutionary fervor, coupled with Napoleon’s strategic genius, made the army exceptionally effective and adaptable.

Corps System: Napoleon's corps system allowed for unprecedented operational flexibility. Each corps operated semi-autonomously, which enabled rapid movements and adaptable tactics. This system was crucial in the rapid and decisive victories that characterized Napoleon's campaigns.

The Danube Campaign and the Battle of Austerlitz

Strategic Mastery at Ulm and Austerlitz: The campaign of 1805 exemplifies Napoleon's military brilliance. By rapidly maneuvering his forces to encircle General Mack at Ulm, he forced a significant Austrian surrender without a major battle. At Austerlitz, known as the "Battle of the Three Emperors," Napoleon cleverly deceived the Austro-Russian forces into a vulnerable position and then capitalized on their strategic errors to win a decisive victory.

Psychological and Material Impact: The victory at Austerlitz not only decimated the Third Coalition's forces but also had a profound psychological impact across Europe. It solidified Napoleon’s reputation as an unbeatable military leader and allowed him to dictate peace terms that reshaped the political boundaries of Europe.

Transformation into the "Great Empire"

Empire Building: Following Austerlitz, Napoleon aggressively expanded French influence across Europe. He created the Confederation of the Rhine as a buffer state, restructured the German states, and placed his family members in positions of power in newly created kingdoms, thereby extending his control across the continent.

Imperial Ambitions and Challenges: While these victories and territorial expansions marked the height of Napoleon’s power, they also sowed the seeds for future coalitions and conflicts. His manipulation of European territories and installation of puppet regimes provoked nationalistic and royalist resentments that would eventually contribute to his downfall.

The events of 1805 were pivotal in transitioning France from a "great nation" to a "Great Empire," showcasing Napoleon’s ability to leverage military victories for political gains. His actions during this year profoundly shaped European politics, setting the stage for further conflicts and the eventual rise of nationalistic movements across the continent.

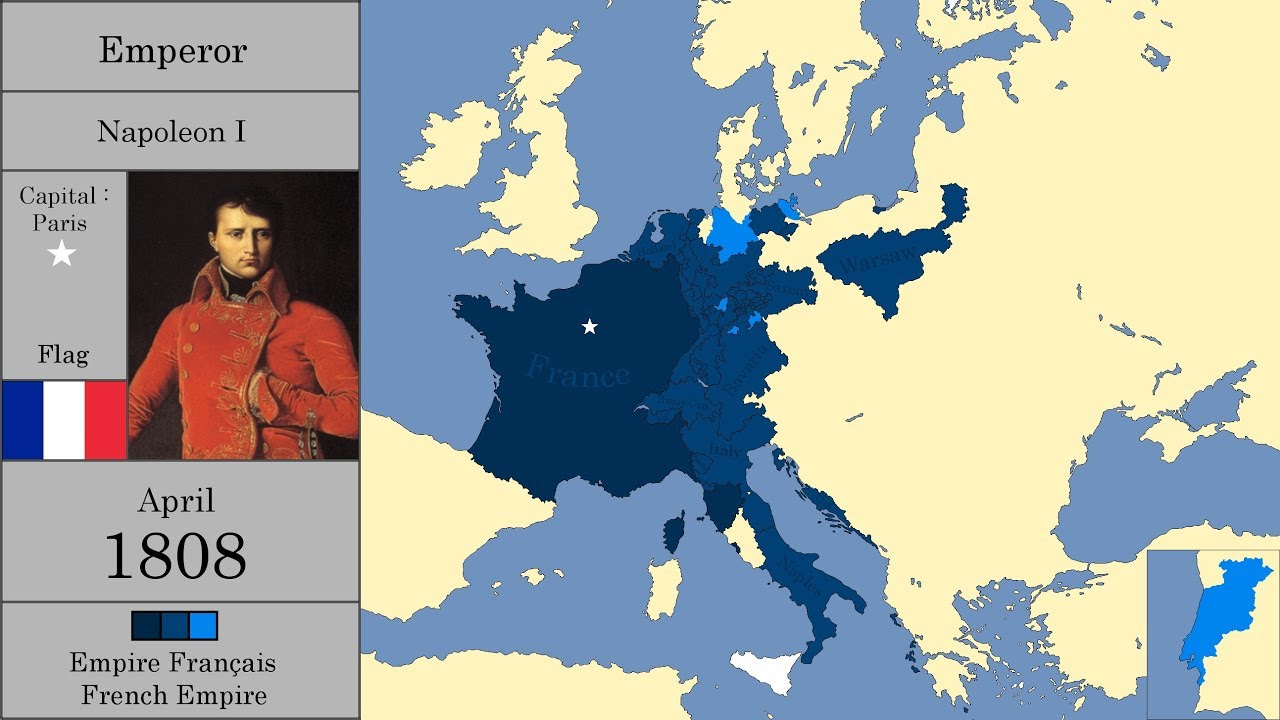

10.) Expanding the Empire

In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte's Empire had expanded to its zenith, encompassing a vast network of territories and satellite states across Europe. However, this expansion also marked the beginning of overextension, where Napoleon's ambitions began to strain the practical limits of his control. Napoleon's inherent boldness, both a strength and a vulnerability, led to critical decisions that ultimately contributed to the fragility of his Empire.

Battles of Jena-Auerstädt (1806)

Prussian Challenge: The Prussian king Frederick William III, pushed by the increasing threat of Napoleon's dominance, issued an ultimatum that escalated into the battles of Jena and Auerstädt. These battles demonstrated the outdated tactics of the Prussian military which relied on precision rather than the speed or flexibility that characterized Napoleon’s strategies.

Napoleonic Tactics: Napoleon's innovative use of the "square battalion" formation allowed rapid and versatile movement across vast distances, outmaneuvering the Prussians. This strategy led to a devastating defeat for Prussia and showcased Napoleon’s ability to adapt and exploit enemy weaknesses efficiently.

Campaign in Poland (1807)

Polish Hopes and Strategy: As Napoleon moved his forces into Polish territories, the Poles saw him as a potential liberator from their partitioners: Prussia, Austria, and Russia. Napoleon's engagements in Poland, especially the significant but bloody standoff at Eylau and the decisive victory at Friedland, solidified his influence in Eastern Europe.

Treaty of Tilsit: The aftermath of these battles led to the Treaty of Tilsit between France, Russia, and Prussia. This treaty dramatically reshaped the European political landscape by severely reducing Prussia's territory and power while ostensibly creating an alliance between Napoleon and Czar Alexander of Russia.

The Continental System

Blockade Against Britain: In an effort to weaken Britain economically, Napoleon enforced the Continental System, a blockade intended to prevent European nations from trading with the British. However, the blockade was unpopular and difficult to enforce, straining relationships with his allies and controlled states.

The Spanish Ulcer (1808)

Overextension into Spain: Napoleon’s decision to intervene in Spanish affairs by installing his brother Joseph as king was a gross miscalculation. The resistance in Madrid and the ensuing widespread guerrilla warfare in Spain drained French resources and shifted European perceptions of Napoleon from a liberator to an oppressor.

Peninsular War: The protracted conflict in Spain, known as the Peninsular War, became a quagmire that sapped French strength. This war exposed the vulnerabilities of Napoleon's military strategies when faced with nationwide popular resistance and unconventional warfare.

Analysis: The Limits of Napoleon’s Empire

Leadership and Overreach: Napoleon’s centralized style of leadership allowed for rapid decision-making and cohesive strategy but also tied the fate of the Empire closely to his personal judgment and capabilities. His aggressive expansion and the personal control he exerted over a vast empire ultimately led to strategic overreach.

Structural Flaws: The lack of a balance of power within the Napoleonic system meant that the sustainability of the Empire hinged entirely on Napoleon’s continuous success and presence. This centralization of power, while effective in building the empire, proved unsustainable in managing its diverse and widespread challenges.

By 1808, it was evident that Napoleon's boldness and strategic brilliance, which had enabled him to construct a vast empire, were the same traits that drove him to overextend his reach, leading to critical vulnerabilities. The Spanish campaign, in particular, marked a turning point where Napoleon's ambition began to exceed his grasp, setting the stage for the eventual resistance and downfall of his Empire.

11.) France During the Empire

Napoleon’s strategy for building his glory and legitimacy at home intricately intertwined with his broader ambitions for a global empire. He skillfully leveraged France's resources and the dedication of its people to reinforce his personal image and the stature of the French Empire. Here’s how he achieved this monumental task:

1. Cultivating an Image of Greatness

Imperial Spectacle: Napoleon understood the power of imagery and spectacle. He orchestrated elaborate ceremonies and created a court culture that mirrored the grandeur of monarchical traditions, all while promoting a new form of nobility based on merit. This blend of old-world charm with revolutionary ideals helped him craft a persona of a modern emperor, rooted in the principles of the Revolution but adorned with the trappings of ancient regime glory.

Architectural Legacy: Napoleon’s transformation of Paris into a neoclassical showcase not only glorified his reign but also aimed to make Paris the capital of Europe. Monuments like the Arc de Triomphe and the expanded Louvre served as physical manifestations of his military and cultural supremacy, embedding his legacy within the urban fabric of Paris.

2. Legal and Social Reforms

Meritocratic Nobility: Unlike the hereditary nobility of the Old Regime, Napoleon’s nobles were primarily military leaders and state officials who had demonstrated exceptional service. This new aristocracy was devoid of traditional privileges but held significant sway and wealth, securing elite support for Napoleon’s regime.

Codification of Laws: The Napoleonic Code was perhaps his most lasting domestic achievement, profoundly reshaping French law by emphasizing legal equality, security of property, and the secular authority of the state.

3. Economic and Military Mobilization

Economic Policy: Napoleon’s economic strategies were dual-edged. On one hand, he fostered the beginnings of an industrial revolution in France by protecting domestic industries from British competition via the Continental System. On the other hand, this blockade also strained economies throughout Europe, including in regions of France dependent on maritime trade.

Conscription and Military Expenditure: The conscription policies under Napoleon were rigorous and often harsh, pulling vast numbers of men into military service. This policy was crucial for sustaining the expansive wars Napoleon pursued but led to widespread resistance and hardship among the French populace.

4. Centralization of Power

Surveillance and Censorship: The Empire marked an era of increased state control over public discourse. Napoleon intensified censorship and surveillance to maintain a narrative of success and suppress dissent, controlling the flow of information to manage public perception.

Infrastructure Improvements: Alongside his more oppressive policies, Napoleon also invested in public works, enhancing Paris’s infrastructure and expanding services that improved daily life for many citizens.

5. The Cost of Empire

Resistance to Authority: The heavy burden of conscription and the economic impacts of ongoing wars and blockades fostered resistance and dissatisfaction. As Napoleon stretched France’s resources to maintain his expansive empire, the strain began to show, culminating in widespread unrest and resistance, particularly in rural areas.

Impact on French Society: While Napoleon’s policies did propel France onto the global stage, they also demanded significant sacrifices from the French people. The very methods that secured his power—rigorous conscription, economic control, and centralization—also sowed the seeds of discontent and resistance that would eventually contribute to his downfall.

In summary, Napoleon’s rule was characterized by a complex interplay between ambitious expansionism and internal consolidation. His efforts to mold France into a dominant European power were marked by significant achievements and profound challenges, reflecting the dual nature of his legacy as both a revolutionary and a ruler.

12.) Living in the Empire

Napoleon's empire-building ambitions were driven by a complex mix of revolutionary zeal and autocratic control. His vision for Europe was transformative, aimed at modernizing and unifying the continent under a centralized, rational system rooted in Enlightenment principles. Here's an exploration of the multifaceted nature of Napoleon's imperial project and its lasting impact on Europe:

1. Modernizer and Liberal Reformer

Legal and Administrative Reforms: Napoleon implemented the Napoleonic Code, which established a clear legal framework across the Empire. This code abolished feudal privileges, established equality before the law, and secured property rights, significantly modernizing the legal systems of the territories he controlled.

Educational Reforms: He reformed educational systems to standardize and improve the quality of education, which aimed to create a more informed and capable citizenry that could serve the empire more effectively.

Economic Integration: Napoleon attempted to integrate the economies of Europe through mechanisms like the Continental System, although this policy also aimed to weaken Britain economically.

2. Cultural Imperialist

Forced Assimilation: Napoleon imposed the French language, legal systems, and other aspects of French culture on conquered regions. While he promoted administrative efficiency and legal uniformity, these policies often disregarded local customs and autonomy, leading to resentment.

Extraction of Resources: Conquered territories were often required to pay heavy taxes, supply men for the army, and provide resources for France’s wars, which strained local economies and fueled discontent among the subjugated populations.

3. Old-style Autocrat

Authoritarian Control: Despite his revolutionary background, Napoleon ruled autocratically. He centralized power in his hands, restricted political freedoms, and used extensive police and military forces to maintain control over his vast empire.

Exploitation of Conquered Peoples: Many of Napoleon's policies were designed to benefit France at the expense of other territories. The burdens of conscription, heavy taxation, and economic exploitation under the Continental System exemplify this exploitation.

4. Impact and Legacy

Resistance and Nationalism: Napoleon’s overreach and the harshness of his rule provoked widespread resistance across Europe, notably in Spain and later in Russia. His actions inadvertently fostered a sense of nationalism in various parts of Europe.

Long-term Reforms: Despite the oppressive aspects of his rule, many of Napoleon’s reforms had lasting benefits. Legal and administrative changes persisted in many areas, influencing the development of modern states in Europe.

Cultural Impact: The diffusion of French culture had a lasting impact on the European cultural landscape, influencing everything from legal systems to local cuisines.

Napoleon's imperial ambitions and the methods he employed to achieve them were marked by contradictions. He was a modernizer who pushed for liberal reforms but also an autocrat who imposed French hegemony at the expense of local cultures and economies. His legacy is thus a complex tapestry of enlightenment and oppression, integration and resistance, which reshaped Europe in ways that are still evident today.

13.) The Russian Campaign

The year 1812 marked a significant turning point in Napoleon's reign, characterized by the catastrophic decision to invade Russia. This decision stemmed from several strategic and personal motivations:

Distraction from Spanish Losses: Napoleon faced ongoing difficulties in Spain, where his forces were bogged down in a grueling conflict that drained resources and weakened his position in Europe. A decisive victory in Russia was seen as a way to shift focus from these losses and reaffirm his strength.

Enforcement of the Continental System: Czar Alexander's refusal to continue the blockade against Britain was a direct challenge to Napoleon’s Continental System, designed to weaken Britain economically by cutting off its trade with Europe. Napoleon saw the invasion as necessary to compel Russian compliance and maintain the integrity of the blockade.

Desire for Ultimate Supremacy: By 1812, Napoleon's ambition to dominate Europe was evident, but securing a definitive victory over Russia would cement his control and potentially bring an end to British resistance by showing the futility of further opposition.

The Russian Campaign

Initial Strategy and Challenges: Napoleon's strategy relied on drawing the Russians into a decisive battle where he could leverage his superior tactics and the Grande Armée’s strength. However, logistical challenges, vast distances, inadequate supplies, and the harsh Russian terrain worked against him.

Russian Scorched Earth Policy: As Napoleon advanced, the Russians retreated, applying a scorched earth policy that deprived the French of vital resources. This strategy extended the supply lines and exacerbated the difficulties faced by the French troops.

Battle of Borodino: This battle, while technically a French victory, failed to decisively defeat the Russian army and did not lead to the capitulation of Czar Alexander, as Napoleon had hoped.

Retreat from Moscow

Occupation and Burning of Moscow: Entering an abandoned Moscow, Napoleon expected to negotiate a peace but found himself in a burnt-out city without provisions or shelter, forcing a retreat.

Disastrous Retreat: The retreat turned catastrophic with the onset of the harsh winter, lack of food, and constant harassment by Russian forces. The army was decimated by cold, disease, and attacks, significantly weakening Napoleon's forces and his position in Europe.

Beginning of the End

Malet Conspiracy: Back in Paris, the Malet conspiracy highlighted the vulnerabilities of Napoleon’s regime and its dependence on his personal presence and military success.

Deteriorating Position: The disastrous Russian campaign, coupled with ongoing struggles in Spain and rising discontent in France, eroded Napoleon's power and prestige. His empire, overstretched and weakened, became vulnerable to new challenges.

The invasion of Russia not only led to monumental military losses but also marked the decline of Napoleon's power, setting the stage for the resurgence of his European adversaries and the eventual coalition that would lead to his downfall. This campaign vividly illustrated the overreach of his imperial ambitions and the limitations of extending power through military means alone.

14.) The Fall of Napoleon and the Hundred Days

As Napoleon reasserted control during the Hundred Days, Europe quickly unified against him once more. This resurgence of opposition underscored the strategic missteps and overarching hubris that had characterized his earlier campaigns, leading to his eventual defeat. Here’s how this period unfolded, leading to the ultimate decline of Napoleon's rule:

Renewed European Alliance: The swift reformation of the coalition against Napoleon highlighted his isolation on the international stage. The Congress of Vienna, initially convened to reorganize territories after Napoleon's abdication, swiftly transitioned into a military alliance against him. This rapid mobilization by Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria showcased the general European consensus against his rule.

Military and Political Maneuvering:

Napoleon's Reforms: Upon his return, Napoleon attempted to regain popular and military support through liberal reforms. He introduced the Additional Act, which limited his powers and promoted liberal principles in an attempt to stabilize his regime.

Recruitment and Military Preparation: Despite the disillusionment and fatigue from continuous wars, Napoleon managed to muster a new army. However, the force was predominantly made up of veterans and new, inexperienced recruits, reflecting the strained resources and waning enthusiasm for prolonged conflict.

Battle of Waterloo:

Final Confrontation: Napoleon’s return culminated in the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815, a decisive confrontation with the allied forces under the Duke of Wellington and Prussian Field Marshal Blücher.

Outcome and Consequences: The defeat at Waterloo was catastrophic for Napoleon. It ended his rule in France, leading to his second abdication and marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Exile and Reflection:

Exile to Saint Helena: Following his defeat, Napoleon was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he spent the last years of his life in relative isolation, reflecting on his reign and writing his memoirs.

Legacy and Historical Debate: Napoleon's impact on Europe was profound and lasting. His legal reforms, particularly the Napoleonic Code, had enduring influences on the legal systems of many European countries and other regions. However, his aggressive foreign policy and the widespread warfare it provoked left Europe exhausted and led to significant shifts in the continent's political landscape.

Napoleon’s ambitious attempts to reshape European politics and society through conquest and reform ultimately faltered due to his overreach and the resilient opposition of combined European forces. His legacy remains complex, embodying the traits of both a revolutionary reformer and an imperial conqueror.

15.) Waterloo

Napoleon's final act, the Hundred Days, vividly illustrated both his formidable will and the limits of his power. Despite his initial success in rallying forces and seizing control once more, his ultimate defeat at Waterloo marked a definitive end to his rule. Here's an overview of the events and their implications:

Preemptive Strike in Belgium: Napoleon's decision to strike in Belgium aimed to divide and conquer the allied forces arrayed against him. His surprise maneuver initially caught the Prussian and British forces off guard, but the lack of coordination among his generals and strategic errors cost him the advantage.

Battle of Waterloo (June 18, 1815):

Tactical Decisions: Napoleon's strategy to attack directly rather than maneuver indirectly (as suggested by his generals) led to a brutal and costly engagement.

Allied Resilience: The allied forces under Wellington and the late arrival of Prussian reinforcements turned the tide against the French. Wellington's defensive setup and the Prussians' timely intervention were decisive.

Outcome: The defeat was catastrophic for Napoleon, leading to high casualties and the ultimate breakdown of his forces.

Aftermath and Abdication:

Return to Paris and Abdication: Napoleon returned to Paris, faced with overwhelming opposition and the rapid advance of enemy forces towards the French capital. Realizing his untenable position, he abdicated again in favor of his son, a move that was largely symbolic as the allies demanded his complete removal.

Exile to Saint Helena: Napoleon was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he spent the last six years of his life. This period was marked by introspection and the dictation of his memoirs, shaping his legacy.

Europe's Reaction and the Congress of Vienna:

Shifting Alliances and Restorations: The Congress of Vienna, which had been ongoing since Napoleon's first abdication, worked to reshape the European political landscape, restoring monarchies and re-drawing borders to balance power and prevent future hegemonic dominance by any single nation.

Legacy and Historical Interpretation: Napoleon's ambitions had reshaped Europe, influencing legal systems, administrative practices, and military strategies. The Napoleonic Code, in particular, left a lasting impact on European legal frameworks.

Napoleon's fall and the subsequent redrawing of Europe's political map ushered in a period of relative peace and stability, known as the Concert of Europe. His legacy, complex and multifaceted, continues to provoke debate and analysis, reflecting his role as both a revolutionary figure and a harbinger of modern statecraft.

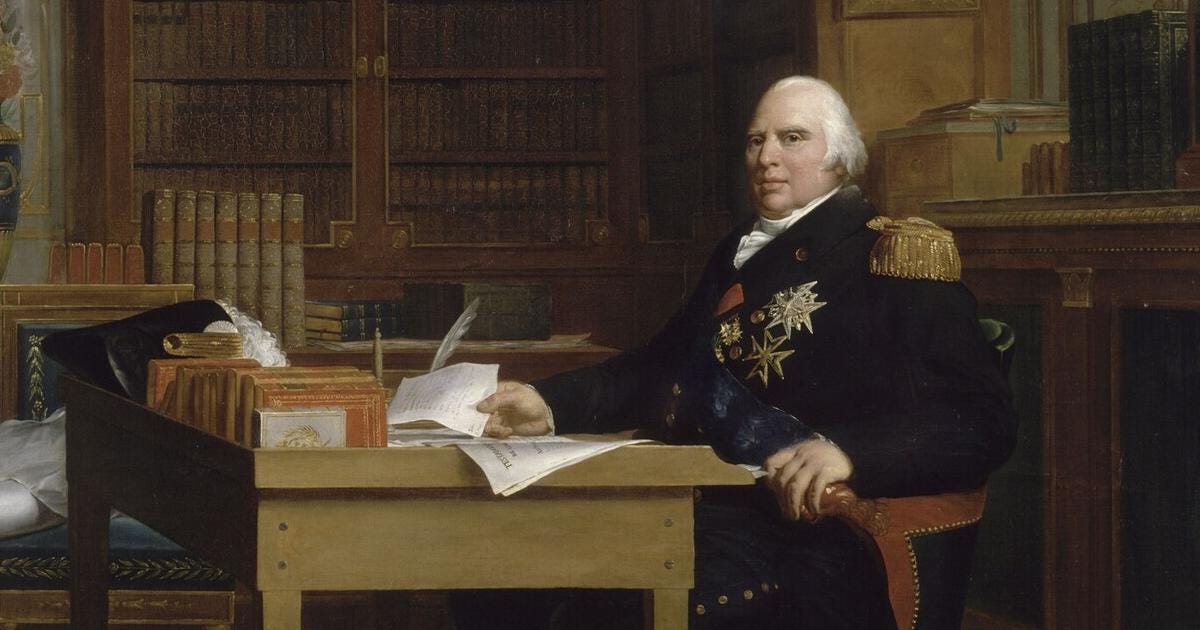

16.) The Restoration Period

The Restoration period in France after Napoleon's fall, marked by the reinstatement of Louis XVIII and later Charles X, exemplified the complex struggles between old regimes and emerging modern political ideologies. This period saw the clash of returning monarchist sentiments and revolutionary principles that had radically transformed French society. Here’s how this era shaped political thought and social structures, along with the emergence of key ideologies:

Social Changes:

End of Feudalism: The revolutionary and Napoleonic eras had dismantled the feudal structures, diminishing the traditional powers of the nobility and clergy.

Rise of the Bourgeoisie: Wealth and social status began to be determined more by economic success than by birth. The bourgeoisie, enriched by the acquisition of national lands and involvement in governance and industry, became influential.

Political Landscape:

Constitutional Monarchy: Louis XVIII attempted to balance royalist desires with the acceptance of revolutionary changes, introducing a constitutional charter that allowed civil liberties and a bicameral legislature, though with significant power still held by the monarchy.

Ultra-Royalists vs. Liberals: The political spectrum saw ultra-royalists who desired a full return to monarchical and aristocratic dominance, and liberals who advocated for constitutional governance, civil rights, and limited monarchy.

Emergence of Key Ideologies:

Conservatism: This ideology emphasized tradition, religion, and hierarchical social order. Prominent figures like Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre articulated conservatism as a response to the upheavals of the Revolution.

Liberalism: Liberals pushed for maintaining the revolutionary gains of civil liberties and representative government. They sought a stable system that prevented both tyranny and mob rule, looking to England’s parliamentary system as a model.

Reaction and Repression:

White Terror: Following the Hundred Days, a wave of violent repression targeted supporters of Napoleon and the revolution, leading to trials and executions.

Restoration of Monarchical Powers: Under Charles X, the monarchy sought to reassert fuller control, culminating in repressive measures against freedom of the press and adjustments in electoral laws to favor the wealthy.

Bonapartism:

Nostalgia and Political Force: Bonapartism evolved as a significant political force, mixing nostalgia for Napoleon’s rule with elements of liberalism and nationalism. It appealed to various segments of society, from veterans and the disaffected bourgeoisie to republicans.

Evolution of Ideals: Initially connected with republican ideals, over time, Bonapartism shifted towards support for strong, centralized authority, evident in the rise of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte.

Continued Political Experimentation:

1830 Revolution: The liberal July Monarchy under Louis-Philippe attempted to stabilize France with a more liberal constitutional framework.

1848 Revolution: The eventual failure of the July Monarchy led to another revolution, bringing about the Second Republic and, ultimately, the rise of Napoleon III, who would echo his uncle’s authoritarian style.

The Restoration period thus reflected a complex interplay of attempts to revert to pre-revolutionary structures and the irreversible changes brought about by two decades of upheaval. It set the stage for modern political ideologies that continued to evolve through the 19th century, influencing not just France but the broader European context.

17.) Legacies

The French Revolution had profound and wide-reaching impacts on the world stage, encapsulating how revolutionary ideas and actions reverberated globally, influencing political ideologies and movements from Latin America to Europe. Here’s a structured overview of the key points discussed:

Global Spread of Revolutionary Ideas:

The imprisonment of the Spanish royal family by Napoleon catalyzed revolutionary movements across Spanish America, leading to independence movements that drew on Enlightenment and revolutionary ideas similar to those that inspired the French.

Influence in Europe:

The Congress of Vienna aimed to suppress the revolutionary spirit by restoring monarchies and traditional structures, yet the ideological seeds of democracy and nationalism sown by the French Revolution proved too resilient, continuing to influence political thought and disruptions like the 1848 revolutions.

Shifts in Ideology and Society:

The era introduced concepts like rights, citizenship, and political participation, which deeply influenced global discourses on governance and individual liberties, challenging old hierarchies and paving the way for modern nation-states and democratic systems.

Legacy of the Napoleonic Wars:

Napoleon’s military campaigns, while destabilizing, also spread revolutionary ideals across Europe, inadvertently setting the stage for the eventual unification movements in Italy and Germany, and affecting military and administrative reforms across the continent.

Revolutionary Legacies and Modern Political Ideologies:

The principles of the Revolution influenced various ideologies, including conservatism, which sought to preserve traditional values; liberalism, advocating for constitutional rule and civil liberties; and socialism, which later emerged as a response to inequalities exacerbated by industrial and post-revolutionary changes.

Impacts on 19th and 20th Century Revolutions:

The revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune further demonstrated the ongoing struggle for social justice and political representation, reflecting the enduring influence of revolutionary ideals.

Human Rights Development:

Post-World War II, the establishment of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 highlighted how revolutionary ideals evolved into global norms that continue to shape international law and human rights advocacy.

Contemporary Reflections on Revolutionary Legacies:

By the bicentennial of the French Revolution in 1989, the global political landscape—marked by events like the fall of the Berlin Wall—still echoed the core revolutionary themes of liberty and rights, underscoring the lasting relevance of the Revolution's ideals.

This exploration underscores how the French Revolution not only reshaped France but also had a lasting impact on the world, fostering ongoing debates and developments in political thought, rights, and governance.

Source: Living the French Revolution and the Age of Napoleon

18.) Napoleon' as a Genius Strategist

Napoleon Bonaparte is celebrated for his innovative military tactics and strategic acumen, which allowed him to dominate European battlefields for over a decade and establish an empire that spanned much of the continent. Here’s an overview of the key tactical and strategic principles that underpinned his success:

Key Tactics and Strategies

1. Speed and Mobility:

Rapid Movements: Napoleon emphasized speed in movement, which allowed him to surprise and outmaneuver slower-moving enemies. His marches were often faster than those of his enemies, giving him the advantage of initiative.

Central Position: By moving quickly, he could often place his forces in a central position between divided enemy forces, allowing him to defeat them in detail, one by one.

2. Use of the Corps System:

Flexible Corps: Napoleon reorganized the French army into corps, each a self-contained unit capable of independent action. This system provided operational flexibility and logistical autonomy. Corps could march separately and then concentrate quickly for a battle, enhancing their ability to maneuver and sustain themselves.

Integrated Arms: Each corps had a mix of infantry, cavalry, and artillery, enabling it to engage the enemy independently or support other corps effectively.

3. Massed Artillery:

Artillery as the Key to Battle: Napoleon often used artillery to soften up the enemy before sending in infantry and cavalry. He concentrated his guns to create a “grand battery” that could breach enemy lines and cause significant disruption and casualties.

Mobile Artillery: He also improved the mobility of artillery, allowing it to be redeployed rapidly to support dynamic battlefield conditions.

4. Decisive Engagement:

Seeking the Decisive Battle: Unlike other commanders who might seek territorial gains or protracted campaigns, Napoleon often aimed for a decisive victory that would destroy the enemy's capacity to fight. He sought to engage and annihilate the main body of the enemy army, believing that political objectives could best be achieved by first achieving total military victory.

5. Psychological Warfare and Morale:

Inspiring Leadership: Napoleon was adept at inspiring his troops, often visiting the front lines and ensuring his soldiers saw him in action. His presence motivated his men and increased their willingness to fight.

Use of Ideology: He also used the principles of the French Revolution — such as liberty, equality, and fraternity — to inspire his troops and undermine enemies, particularly in territories with oppressive feudal regimes.

What He is Known For

Innovative Reforms: Napoleon is known for military innovation, but also for administrative, legal, and societal reforms in France and the territories he conquered, many of which have lasting impacts, like the Napoleonic Code.

Napoleonic Warfare: His style of warfare became known as Napoleonic warfare, characterized by aggressive offensives, rapid movement, flexible use of artillery, and strategic concentration of forces.

Lessons from Napoleon

Importance of Logistics: Napoleon famously stated, “An army marches on its stomach,” underscoring the critical importance of logistics in military campaigns.

Flexibility and Adaptability: His use of the corps system highlighted the importance of having adaptable and self-sufficient units within a larger strategic framework.

Psychological and Ideological Dimensions: His campaigns demonstrate how leadership and the moral aspect of warfare can significantly impact outcomes.

Limits of Overextension: His eventual downfall — particularly during the invasion of Russia — serves as a cautionary tale of the dangers of overextension and the limits of military power against determined resistance and harsh environments.

Napoleon’s tactics and strategies have been studied extensively in military academies around the world and continue to influence modern military thinking. His successes and failures alike offer valuable lessons in the complexity and dynamics of strategic planning and execution.