1.) Overview

The Tao Te Ching, a foundational text of Taoism attributed to the sage Laozi, expounds the philosophy of the Tao (pronounced "Dao"), which can be understood as the "Way" or the "Path." This ancient Chinese philosophy is centered on principles that guide not only personal conduct but also the governance of societies. To fully grasp the Way of the Tao, it's essential to explore the core principles and virtues associated with it.

1. The Tao as the Fundamental Principle: At the heart of Taoism is the concept of the Tao itself. The Tao is often described as the unnameable, formless, and all-encompassing source of everything in the universe. It's the underlying order that governs all of existence. The Tao is characterized by qualities such as simplicity, harmony, and balance.

2. Virtues of the Tao:

Simplicity: Simplicity is a key virtue in the Way of the Tao. It encourages individuals to lead uncomplicated lives, free from unnecessary desires and attachments. By simplifying one's existence, one can achieve greater clarity and harmony.

Humility: Humility is another central virtue. Taoism teaches that true wisdom and understanding come from acknowledging one's limitations and not boasting about one's achievements. Humble individuals are open to learning and growth.

Compassion: Compassion is an essential aspect of following the Tao. It calls for empathy and kindness toward all living beings. Compassionate actions promote harmony and reduce conflict in society.

Selflessness (Wu Self): Selflessness, or "wu self" in Chinese, is a core concept in Taoism. It encourages individuals to transcend their ego and self-centered desires. The idea is to let go of the self as the primary focus and instead cultivate a sense of interconnectedness with all beings and the universe. Selflessness leads to compassion and empathy for others, as one recognizes that their well-being is intimately tied to the well-being of others.

Non-Interference: Taoism emphasizes non-interference or wu wei, which means "actionless action" or "effortless doing." This principle encourages individuals to act spontaneously and without force, allowing events to unfold naturally. It doesn't mean inaction but rather aligning with the natural flow of life.

Flexibility: Being flexible and adaptable is crucial in Taoism. Just as water can adapt to any container, Taoists believe that individuals should be adaptable in their approach to life's challenges. This virtue promotes resilience and avoids rigid thinking.

Balance: Balance is the key to harmony in Taoism. It encourages individuals to find equilibrium in all aspects of life, whether it's work and leisure, yin and yang (opposing but complementary forces), or various personal attributes.

Moderation: Moderation is closely related to balance. It teaches that excess and extremes should be avoided. By practicing moderation, individuals can maintain physical and mental well-being.

Detachment: Detachment doesn't mean apathy but rather the ability to let go of attachments to material possessions, desires, and outcomes. This allows individuals to experience inner peace and freedom.

Acceptance of Change: The Tao teaches that change is inevitable, and individuals should accept it rather than resist it. By embracing change and going with the flow, one can lead a more fulfilling life.

3. The Way of the Sage: In Taoism, a sage is an individual who embodies these virtues and lives in harmony with the Tao. Sages are humble, compassionate, and wise. They do not seek recognition or personal gain and are dedicated to the well-being of others and the world.

4. Governance and the Tao: The Way of the Tao is not limited to personal conduct but also extends to governance. The concept of wu wei, or non-interference, suggests that leaders should govern with minimal intrusion, allowing society to find its natural balance. Leaders who follow the Tao prioritize the welfare of their people over personal power and prestige.

In conclusion, the Way of the Tao is a profound philosophy that offers guidance for living a virtuous and harmonious life. It emphasizes simplicity, humility, compassion, and many other virtues that promote personal well-being and societal harmony. Following the Tao is not about rigid rules but rather a path of self-discovery and aligning with the natural order of the universe. By embracing these principles, individuals can cultivate wisdom, inner peace, and a deep sense of connection with the world around them.

2.) The Tao or Way

The concept of the Tao has two primary aspects:

Way of Living: The Tao is a guide for how to live a harmonious and balanced life. It provides principles and values that encourage simplicity, humility, compassion, and living in accordance with the natural order of the universe.

Essence of Existence: The Tao is also seen as the fundamental and unchanging essence or source of all things. It's the creative force or originator of the universe. In this sense, it represents the ultimate reality or the underlying principle behind all of existence.

So, the Tao encompasses both a way of living and a profound understanding of the essence that underlies the existence of everything in the universe. It's a comprehensive concept that offers both practical guidance for daily life and a deep philosophical understanding of the cosmos.

3.) Wu Wei

Flowing Like Water: Understanding Wu Wei through the Analogy of Adaptation

Introduction

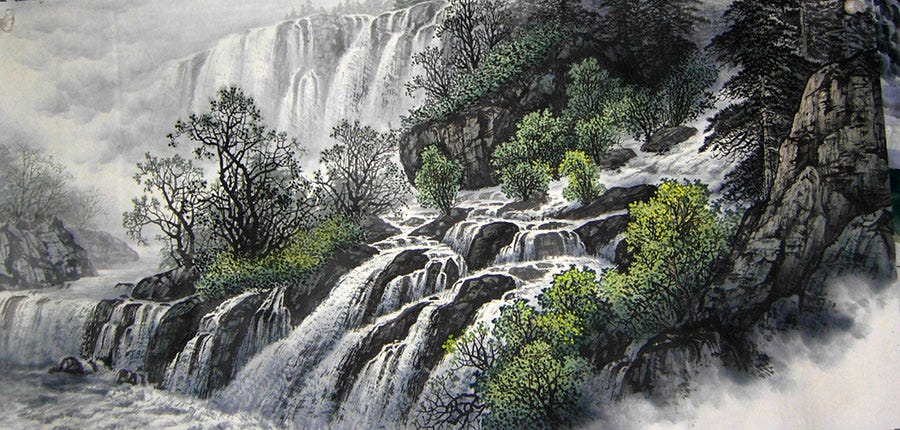

In the realm of ancient Chinese philosophy, the concept of Wu Wei stands as a fundamental pillar of Taoism. Wu Wei, often translated as "effortless action" or "non-doing," encourages us to live in harmony with the natural flow of the Tao, the underlying principle of the universe. To grasp this profound idea, consider the analogy of water adapting to rocks in a riverbed.

The Nature of Water

Water is an extraordinary element. It possesses the remarkable ability to adapt to its surroundings, seeking the path of least resistance. It flows effortlessly, gently carving its way through the earth's contours. Water doesn't confront obstacles head-on or forcefully attempt to change them; it yields, absorbs, and continues its journey around them.

The River's Wisdom

Imagine a river coursing through a rugged landscape, its waters gracefully weaving around massive boulders and jagged rocks. In doing so, it doesn't struggle or fight; it simply follows the natural contours of the terrain. The river's wisdom lies in its adaptability. It doesn't resist obstacles; it embraces them, flowing around and over them with ease.

The Parallels with Wu Wei

Now, let's draw parallels between the river's behavior and the philosophy of Wu Wei:

Adaptation over Confrontation: Just as the river adapts its course to navigate around rocks, Wu Wei encourages us to adapt to life's circumstances rather than confront them forcefully. It's about finding the path of least resistance, both externally and internally.

Effortless Flow: Like water's gentle flow, Wu Wei emphasizes acting without unnecessary effort or struggle. It's about allowing things to unfold naturally, rather than trying to control every aspect of our lives.

Acceptance and Harmony: Water accepts the landscape as it is, in all its rugged beauty. Similarly, Wu Wei teaches us to accept the world and ourselves as they are, fostering harmony and inner peace.

Flexibility and Resilience: Water's adaptability makes it resilient. Wu Wei invites us to be flexible in the face of challenges, bounce back from setbacks, and remain unbroken like a river flowing around obstacles.

Non-Resistance: Water doesn't resist; it yields. Wu Wei encourages us to let go of resistance and embrace the present moment. It's about accepting reality without judgment.

Conclusion

In the analogy of water adapting to rocks, we find a profound illustration of Wu Wei's wisdom. Just as water's adaptability and gentle flow make it a powerful force in nature, the practice of Wu Wei can transform our lives. By embracing its principles—adapting, flowing effortlessly, accepting, and yielding—we can navigate life's challenges with grace and find a deeper sense of harmony with the Tao. So, like water, let's strive to flow effortlessly and adapt to the ever-changing landscape of our existence.

4.) Going with the Flow

Here's how you can understand and practice "going with the flow" from a Taoist perspective:

1. Embrace the Natural Rhythm: Taoism encourages individuals to observe the natural rhythms and cycles of life. Just as nature has its seasons, cycles, and rhythms, so do our lives. Embrace these changes rather than resisting them. When you encounter obstacles or challenges, consider them part of the natural ebb and flow of life.

2. Cultivate Wu Wei: Practice "wu wei" by letting go of the need to control every aspect of your life. Instead of forcing outcomes, allow things to unfold naturally. This doesn't mean you shouldn't take action when necessary, but your actions should be in harmony with the situation, like a skilled sailor adjusting their sails to catch the wind.

3. Trust Intuition: Taoism values intuitive wisdom. Trust your inner guidance and instincts. By listening to your intuition and being in tune with your inner self, you're more likely to make decisions and take actions that align with the flow of the Tao.

4. Be Present: Living in the present moment is essential in Taoism. When you're fully present and mindful, you're better able to perceive the subtle cues and opportunities that the Tao presents. It's in the present moment that you can make choices that harmonize with the natural flow.

5. Adapt and Flexibility: Water is often used as a metaphor in Taoism. Water is soft and yielding, yet it can erode mountains over time through its persistence. Be adaptable and flexible, like water, in the face of challenges. Adjust to circumstances rather than resisting or opposing them.

6. Let Go of Attachments: Attachments to specific outcomes or possessions can lead to suffering when they are not met. Taoism advises letting go of excessive attachments, as this can free you from unnecessary burdens and allow you to move more fluidly with the flow of life.

In essence, "going with the flow" in Taoism means aligning yourself with the natural order of the universe, acting in harmony with it rather than against it. It's about finding balance, embracing change, and allowing life to unfold without unnecessary resistance. By doing so, you can experience a sense of peace, fulfillment, and connectedness with the Tao.

5.) The Unity of Opposites: Yin and Yang

The philosophy and practice of Yin and Yang, deeply rooted in Daoism, encompass a profound understanding of the interdependence of opposites and the fundamental unity underlying the universe. This concept, symbolized by the Yin Yang symbol, is not only central to Daoism but also influences various aspects of Chinese culture.

At the heart of the Yin and Yang philosophy is the recognition of the interdependence of opposites. In this worldview, day and night, good and evil, and other opposing forces cannot exist in isolation; they are inherently connected and reliant on one another. The iconic Yin Yang symbol visually embodies this concept, with the contrasting black and white halves blending into each other at their borders. This merging of opposites signifies that one cannot exist without the other. Moreover, the presence of small dots of the opposite color within each half serves as a reminder that there is always a trace of the opposite force within each aspect of existence.

The interaction and balance of Yin and Yang are believed to give birth to everything in the universe. This includes not only physical phenomena but also aspects of human life, such as health. Traditional Chinese medicine, for instance, assesses a person's well-being based on the equilibrium of Yin and Yang within their body. When these forces are in harmony, it signifies good health, while an imbalance may lead to illness. This holistic approach to health underscores the profound influence of Yin and Yang on daily life and well-being.

Importantly, the philosophy of Yin and Yang is not limited to Daoism but has far-reaching implications for Chinese culture as a whole. Its principles have permeated various aspects of Chinese thought, including art, philosophy, and even martial arts. This enduring influence demonstrates the enduring significance of this concept throughout Chinese history.

Interestingly, the concept of Yin and Yang, with its emphasis on the interdependence of opposites, bears some similarity to the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus. Both traditions acknowledge the dynamic and ever-changing nature of reality. However, while Yin and Yang found resonance and practical application in the East, Heraclitus' similar ideas were largely dismissed in the Western philosophical tradition, highlighting the contrasting paths of development in these two cultural spheres.

Yin and Yang

Yin:

Yin is often associated with qualities such as darkness, passivity, receptivity, coolness, and femininity.

It is symbolized by the black part of the Yin Yang symbol.

Yin represents the receptive and nourishing aspect of existence. It is the hidden, yielding, and tranquil force in nature.

Examples of Yin elements include the moon, water, the night, and the earth.

Yang:

Yang is associated with qualities such as light, activity, assertiveness, warmth, and masculinity.

It is symbolized by the white part of the Yin Yang symbol.

Yang represents the active, energetic, and dynamic aspect of existence. It is the visible, assertive, and vigorous force in nature.

Examples of Yang elements include the sun, fire, the day, and the heavens.

The key principle of Yin and Yang is that these two forces are not in opposition to each other but rather complementary and interdependent. They exist in a state of constant flux and change, and it is their interaction and balance that give rise to all phenomena and experiences in the universe. Neither Yin nor Yang is superior to the other; instead, they coexist and create harmony when in balance, and disharmony when one dominates the other. This concept underscores the idea that balance and harmony are essential for well-being and the functioning of the natural world.

Harmony with Nature: Taoism emphasizes living in harmony with nature. Nature itself is a manifestation of the unity of opposites—storms and calm, growth and decay, creation and destruction. By observing nature's cycles and embracing them, we learn to accept the coexistence of opposites in our own lives.

Practical Applications of Taoist Wisdom

Embrace Balance: In our fast-paced lives, it's easy to be consumed by extremes. Taoist wisdom encourages us to seek balance. For instance, if we are overwhelmed by work, we can counterbalance it with periods of rest and relaxation. By acknowledging the unity of opposites, we prevent burnout and enhance overall well-being.

Practice Wu Wei: In our goal-oriented society, we often believe that constant striving and effort are necessary for success. Taoism teaches us to discern when to act and when to allow things to unfold naturally. By practicing Wu Wei, we reduce stress and improve our decision-making.

Cultivate Compassion: The unity of opposites extends to human relationships. Just as Yin and Yang coexist, we encounter a diverse range of personalities and viewpoints. Taoism encourages us to approach others with compassion and understanding, recognizing that our differences enrich our collective experience.

Accept Impermanence: Life is a continuous cycle of birth and death, gain and loss. Taoism reminds us that these opposites are interconnected and inevitable. By accepting the impermanence of all things, we can navigate life's challenges with greater equanimity.

Connect with Nature: Spend time in nature to observe the unity of opposites firsthand. Watch the changing seasons, the ebb and flow of tides, and the rising and setting of the sun. These natural rhythms can inspire us to embrace the cyclical nature of our own lives.

6.) Emptiness

The concept of emptiness, often referred to as "emptiness" or "wu" (無) in Taoism (Daoism), is a fundamental and abstract philosophical idea that has profound implications for understanding the nature of reality and the Tao (Dao) itself. Here's an explanation of the Taoist concept of emptiness:

Emptiness as the Essence of the Tao: In Taoism, the Tao is often described as the ultimate source and principle of all things. It is formless, nameless, and transcendent. Emptiness is seen as the essence of the Tao. It signifies a state of pure potentiality, a void that contains the infinite possibilities of existence. This emptiness is not a lack or absence but rather a profound and dynamic state of being.

Non-Duality: Emptiness in Taoism is closely related to the concept of non-duality, which suggests that opposites and distinctions are ultimately illusory. Within emptiness, there is no separation between things; it is the ground of unity where all dualities, such as good and bad, self and other, dissolve. Emptiness is the space in which these dualities arise and return.

The Ungraspable Nature of the Tao: Emptiness is often associated with the idea that the Tao cannot be grasped or comprehended by conventional thinking or language. It transcends human understanding and categorization. Any attempt to define or limit the Tao diminishes its true essence.

Freedom and Spontaneity: Emptiness is also connected to the concept of wu wei, which means "non-action" or "effortless action." It suggests that when one aligns with the emptiness of the Tao, actions flow naturally and spontaneously without attachment or striving. It's like allowing the current of a river to carry you rather than resisting it.

Transformation and Creativity: Emptiness is not a static void but a dynamic and creative force. It is the source of all potentialities and transformations in the universe. Within emptiness, everything arises and returns, making it the wellspring of change and renewal.

Paradox and Mystery: Emptiness introduces a paradoxical and mysterious aspect to Taoism. It challenges conventional thinking and invites individuals to explore the depths of existence beyond ordinary concepts and categories. Embracing this paradoxical nature is believed to lead to profound insights and wisdom.

Freedom from Attachments: Emptiness encourages individuals to let go of attachments and rigid beliefs. By recognizing the emptiness within and around them, Taoists seek freedom from the limitations imposed by attachments to material possessions, desires, and ego.

Practicing Emptiness through Meditation

Practicing emptiness, often associated with Zen Buddhism and Taoism, is a process of letting go of attachments, ego, and preconceptions to experience a state of openness and clarity. Here's a step-by-step concise guide on how to practice emptiness:

Meditation Preparation:

Find a quiet and comfortable space for meditation.

Sit in a relaxed but upright posture, either on a cushion or a chair.

Close your eyes, take a few deep breaths, and relax your body and mind.

Focus on the Breath:

Begin your meditation by focusing on your breath. Pay attention to the natural rhythm of your inhalations and exhalations.

Use your breath as an anchor to bring your attention to the present moment.

Let Go of Thoughts:

As thoughts arise, acknowledge them without judgment, and then gently let them go.

Imagine your thoughts as clouds passing through the clear sky of your mind. Allow them to drift away.

Release Attachments:

Identify any attachments or preoccupations in your mind. These can be desires, worries, or fixed beliefs.

Consciously let go of these attachments. Recognize that they are temporary and do not define your true self.

Observe Sensations and Emotions:

Pay attention to physical sensations and emotions as they arise during meditation.

Observe them with detachment, as if you are an impartial observer. Avoid getting entangled in them.

Empty the Mind:

Gradually, with continued mindfulness of your breath and thoughts, aim to empty your mind of clutter and distractions.

Strive for a state of mental stillness and clarity.

Cultivate Presence:

Embrace the present moment fully. Let go of concerns about the past or future.

Experience a sense of presence and spaciousness in the here and now.

Embrace the Void:

As your meditation deepens, you may encounter a sense of emptiness or void. This is not something to fear but to embrace.

Recognize that this emptiness is not a lack but a source of profound potential and freedom.

Non-Attachment to Self:

Explore the concept of non-self (anatta). Understand that your sense of self is not fixed but arises from conditions.

Let go of attachment to your ego or self-identity.

Daily Life Integration:

Emptiness practice isn't confined to meditation. Carry this mindfulness into your daily life.

Continuously observe attachments and ego-driven thoughts and release them.

Compassion and Connection:

Use the clarity and openness cultivated through emptiness practice to develop compassion and empathy for others.

Recognize the interconnectedness of all beings.

Regular Practice:

Emptying the mind is a skill that deepens with practice. Set aside time for regular meditation sessions to refine your ability to let go and experience emptiness.

Remember that the practice of emptiness is a journey, and progress may be gradual. Be patient with yourself and stay committed to the path of inner exploration and liberation from attachments. Over time, you can experience greater clarity, peace, and freedom in your life.

7.) Principles for Life

Embrace Simplicity: Simplify your life by letting go of unnecessary desires, possessions, and complications. Emptiness reminds us that true fulfillment often comes from simplicity.

Practice Non-Attachment: Avoid becoming overly attached to material things, achievements, or personal identity. Emptiness teaches us to detach from ego-driven desires and find contentment in the present moment.

Flow with Life: Embrace the principle of wu wei, or "effortless action." Allow life to unfold naturally, like a river's current. Instead of forcing outcomes, go with the flow and trust the process.

Recognize Unity: Understand that all things are interconnected and part of the same underlying reality. Emptiness encourages you to see beyond divisions and dualities and appreciate the unity of existence.

Embrace Change: Emptiness is the source of transformation and creativity. Embrace change as a natural part of life. See challenges as opportunities for growth and renewal.

Let Go of Labels: Avoid rigid categories and definitions. Recognize the limitations of language and concepts in describing the profound mysteries of existence.

Live in the Present: Shift your focus from past regrets and future anxieties to the present moment. Emptiness invites you to experience life fully in the here and now.

Cultivate Inner Peace: By aligning with emptiness, you can find inner peace and serenity. Let go of inner conflicts and strive for a calm and centered state of mind.

Respect Nature: Taoism encourages harmony with nature. Embrace the natural rhythms of life, and learn from the simplicity and balance found in the natural world.

Embrace Paradox: Recognize that life is filled with paradoxes and mysteries. Embrace the unknown and find wisdom in the profound and the contradictory.

Incorporating these principles into your life can lead to a deeper understanding of the Taoist concept of emptiness and help you live a more balanced, harmonious, and fulfilling life.

8.) The Tao Te Ching

Chapter 1: Understanding the Tao “The Way”

Laozi starts by emphasizing that the true Tao, the fundamental principle of the universe, cannot be fully expressed or grasped through words or concepts. The Tao that can be spoken or named is not the eternal and unchanging Tao. This suggests that the Tao is beyond the limitations of language and thought.

The Tao is described in two aspects: nameless and named. When it's nameless, it is the originator of everything in the universe. When it's given a name, it becomes the source or mother of all things. This duality highlights the paradoxical nature of the Tao.

To understand the deep mystery of the Tao, one must be without desire. Desire limits our perception to the surface, preventing us from grasping the profound essence of the Tao. Without desire, we can delve into the true nature of reality.

Laozi concludes that these two aspects of the Tao, nameless and named, are essentially the same. They are part of the "Mystery," and the deepest understanding of this mystery is the gateway to all that is subtle and wonderful. This suggests that by transcending duality and conceptualization, one can attain a deeper understanding of reality.

Chapter 2: The Unity of Opposites

This chapter begins by highlighting the duality present in the world. People recognize beauty because they also understand ugliness. They appreciate skill because they comprehend the lack of skill. This dualistic thinking is a fundamental aspect of human perception.

Laozi explains how opposites and contrasts give rise to each other. Existence and non-existence, difficulty and ease, length and shortness, height and lowness, musical notes and tones, being before and behind – these pairs are interdependent. Each concept gains meaning through its relation to its opposite.

Quotes

“So it is that existence and non-existence give birth the one to (the idea of) the other; that difficulty and ease produce the one (the idea of) the other; that length and shortness fashion out the one the figure of the other; that (the ideas of) height and lowness arise from the contrast of the one with the other; that the musical notes and tones become harmonious through the relation of one with another; and that being before and behind give the idea of one following another.”

Chapter 3: Leaders Should Discourage Desires

Laozi describes the sage's governing style, which involves emptying the minds of the people (freeing them from excessive desires and ambitions), ensuring their physical well-being, reducing their willpower (making them less prone to excessive ambition), and strengthening their inner character.

Abstinence from Action: The sage encourages people to be without excessive knowledge and desire, and even those who possess knowledge should refrain from presuming to act upon it. This abstinence from excessive action and ambition leads to a state of good order throughout society.

In simple terms, this chapter conveys the idea that a wise leader or ruler doesn't overly promote exceptional individuals or stimulate excessive desires among the people. Instead, they focus on fostering contentment, simplicity, and inner strength, which leads to a more harmonious and orderly society.

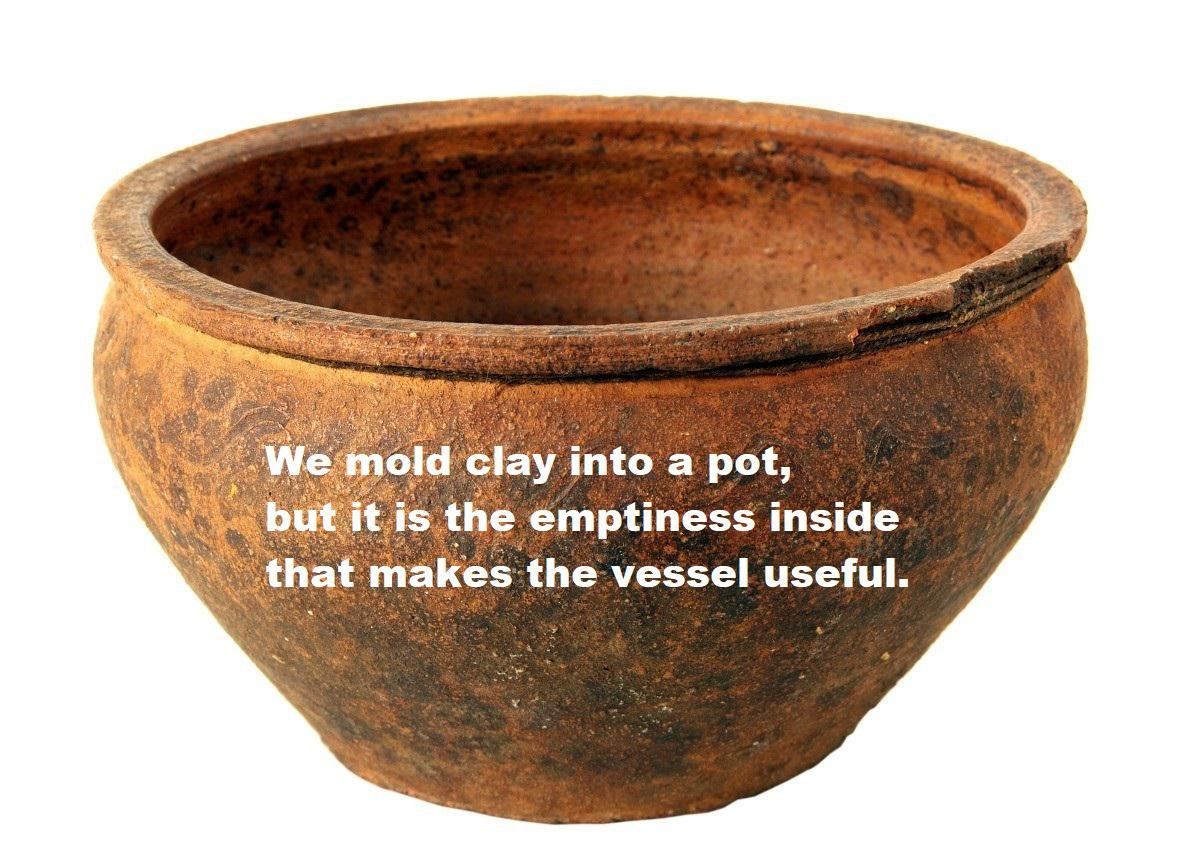

Chapter 4: Humility, Purity and Stillness

In simple terms, this chapter conveys the idea that the Tao is a profound and fundamental force, much like the emptiness of a vessel that gives it purpose. To align with the Tao, one should let go of excess, ego, and complexity, seeking a state of purity, stillness, and humility. The passage also emphasizes the enigmatic and timeless nature of the Tao, which is beyond human knowledge and even traditional notions of divinity.

Chapter 5: Living Dispassionately in Harmony with the Tao

Laozi begins by stating that both heaven and earth do not act out of a desire to be benevolent. Instead, they operate in a natural and impartial way, much like how grass is treated. This suggests that the natural world operates without any deliberate intention to be good or bad; it simply follows its inherent order.

Laozi then extends this idea to the sages or wise individuals. Just like heaven and earth, they don't act with the intention of being benevolent or kind. Instead, they interact with people in a way that aligns with the natural order, similar to how grass is treated. This implies that wise individuals act in harmony with the Tao, without imposing their own desires or judgments.

Chapter 6: The Foundations of Existence

This chapter highlights the idea of an enduring and foundational aspect of nature, symbolized by the valley and associated with the feminine qualities of gentleness and continuity. It suggests that this aspect of nature is essential for the existence and harmony of the world and should be respected and used gently, without causing harm.

Chapter 7: The Selflessness of Existence

This passage teaches that heaven and earth endure because they don't act selfishly; they work in harmony with the larger universe. Likewise, the sage places their own desires last, and by doing so, they achieve their objectives because they are aligned with the natural order. It emphasizes the value of selflessness and aligning with a greater purpose or order in life.

Chapter 8 - The Tao is like water - Humble, adaptable and harmonius

This chapter emphasizes the idea that the highest form of excellence is like water. It benefits others naturally, without contention, and doesn't seek the spotlight. Excellence can be found in various aspects of life, including where you live, your state of mind, your associations, governance, the way you handle tasks, and the timing of your actions. Additionally, when someone with true excellence doesn't insist on a higher position, they are rarely criticized. This chapter promotes the virtues of humility, adaptability, and harmony with the natural order.

Chapter 9 - Avoid Excess, especially Arrogance

In simple terms, this passage teaches that it's better to leave things partially unfilled than to overburden them. Excess can lead to problems. Additionally, accumulating wealth and honors can lead to arrogance, which invites negative consequences. When you've achieved your goals and recognition, it's wise to maintain humility and not let success inflate your ego. This aligns with the natural way of things, which values balance and modesty.

Chapter 10 - Inner Harmony

In simpler terms, this passage encourages inner harmony by uniting different aspects of the self, achieving a state of simplicity and purity. It also speaks to leadership, suggesting that a wise leader can rule without appearing to exert forceful control, much like the gentle workings of nature. Such a leader may seem unassuming but possesses profound wisdom and understanding. Finally, it describes the Tao as a force that creates and nourishes the world while remaining humble and mysterious in its actions.

Chapter 11 - The Importance of Emptiness

In simple terms, this passage conveys the idea that in various aspects of life, the value and usefulness of things often depend on their emptiness or hollowness. The empty space allows for functionality and adaptation, and what exists physically is only valuable when it serves a useful purpose. This principle reflects the Taoist concept of embracing emptiness and simplicity to find true utility and value in life.

Chapter 12 - Simplicity and Contentment

The Senses and Desires: Laozi begins by pointing out how our senses can lead to desires and, if unchecked, can have negative consequences:

Sight (color) can lead to attachment and distraction.

Hearing (music) can distract the mind and make one deaf to more important things.

Taste (flavors) can lead to overindulgence.

Pursuits like chariot racing and hunting can drive people to madness.

Seeking rare and unusual things can corrupt behavior.

The Sage's Approach: Laozi suggests that the wise person (sage) focuses on satisfying basic needs, such as the hunger of the belly, rather than chasing after insatiable desires of the eyes (visual attractions). The sage recognizes that pursuing simpler, essential needs can lead to contentment and harmony.

In simple terms, this passage advises that our senses can lead us astray if we indulge them excessively in the pursuit of desires. Instead, the wise person prioritizes basic needs and avoids the trap of endless desires for material or sensory pleasures. This aligns with the Taoist principle of simplicity and contentment.

Chapter 13 - Balance in Leadership

This passage teaches that both positive and negative situations should be approached with a balanced perspective. Favor and disgrace are interconnected, as are honor and calamity. The wise leader treats the kingdom with care and responsibility, similar to how they treat themselves, and this ensures effective governance. It emphasizes the importance of humility and balance in leadership.

Chapter 14 - The Elusiveness of the Tao

In simple terms, this passage conveys the idea that the Tao is elusive and cannot be easily described or comprehended. It's consistent, silent, and subtle. The Tao is beyond our usual distinctions of light and dark, and it's ever-present yet nameless. By aligning with its ancient principles, we can find guidance and clarity in the complexities of the present.

Chapter 15 - Traits of Taoist Masters

The Skilful Masters: Laozi begins by praising the ancient masters of the Tao. These wise individuals possessed deep understanding and subtle insight into the mysteries of the Tao. They were so profound in their knowledge that they seemed beyond the comprehension of ordinary people. Laozi expresses his intention to describe what these masters appeared to be like.

Description of the Masters: Laozi goes on to describe the appearance and demeanor of these masters:

They appeared cautious, like someone walking through a cold stream in winter.

They seemed hesitant, like someone who is afraid of their surroundings.

They carried themselves with gravity, like a guest showing respect to a host.

They were fleeting, like melting ice.

They were unpretentious, like raw, unshaped wood.

They appeared open and vacant, like a valley.

They were unassuming, like muddy water.

Clearing Muddy Water: Laozi poses a question: Who can make muddy water clear? He suggests that if you leave the water still, it will gradually become clear. Likewise, achieving a state of rest or tranquility is not something you force but something that arises naturally through allowing movement to cease.

Humbling the Self: Laozi concludes by stating that those who follow the Tao do not seek to inflate their own egos. By not being full of themselves, they can afford to appear worn and incomplete. This humbleness and lack of self-importance allow them to align with the Tao.

In simpler terms, this passage praises the wisdom of ancient Taoist masters who possessed deep insights into the Tao. They appeared cautious, humble, and unassuming, much like the natural world. The passage also emphasizes the importance of stillness and humility, as well as the idea that clarity and tranquility arise naturally when we let go of excessive striving and ego.

Chapter 16 - All things Rest

In simpler terms, this passage teaches that embracing vacancy (an open mind) and stillness (calmness) is essential. All things go through cycles of activity and rest, like plants growing and returning to their roots. Understanding and aligning with this natural order is a sign of intelligence and leads to a noble character. This character, akin to heaven, allows one to possess the Tao, resulting in endurance and immunity from decay and danger.

Chapter 17 - Rulers and the Tao

This passage illustrates the changing dynamics between rulers and the people over time. Initially, rulers were not overtly needed, but as time passed, rulers emerged, and people's attitudes toward them shifted from love to fear and finally to disdain. This transformation in attitude is linked to the rulers' adherence (or lack thereof) to the principles of the Tao. The earliest rulers, despite their success, were modest and didn't claim credit for the people's self-sufficiency.

Chapter 18 - The Cycle of Society

“When the Great Tao (Way or Method) ceased to be observed, benevolence and righteousness came into vogue. (Then) appeared wisdom and shrewdness, and there ensued great hypocrisy. When harmony no longer prevailed throughout the six kinships, filial sons found their manifestation; when the states and clans fell into disorder, loyal ministers appeared.”

In summary, this passage describes a societal cycle: When people deviate from observing the Great Tao, there is a shift toward emphasizing benevolence and righteousness. This shift, in turn, leads to the emergence of wisdom and shrewdness, as well as an unfortunate increase in hypocrisy. Additionally, when harmony breaks down in various social relationships and within larger social entities, virtuous individuals, such as filial sons and loyal ministers, emerge to restore order and harmony. It highlights the interconnectedness of individual behavior and the state of society as a whole.

Chapter 19 - Simplicity and Humility over Intellectual Superiority

This passage encourages a humble and less self-assured approach to knowledge, morality, and governance. It suggests that simplicity, honesty, and humility can lead to a more harmonious and just society, as opposed to relying on intellectual superiority, self-righteousness, or complex strategies. By letting go of these attachments, individuals and leaders can benefit the people greatly.

Chapter 20 - Simplicity and Contentment

This passage reflects on the benefits of simplicity and contentment. Laozi suggests that by renouncing excessive learning and the need to constantly please others, we can avoid troubles. He contrasts his own sense of contentment in simplicity with the busyness and superficiality of ordinary people. Despite feeling different from others, he values the nurturing aspect of the Tao, which represents the source of balance and harmony.

Chapter 21 - The Essence of the Tao

In essence, this passage conveys that the Tao is the ultimate source and foundation of all things. It is mysterious and beyond human comprehension but contains the essences and truths of existence. Everything in the world, with its inherent beauty and endurance, derives from the Tao. Laozi invites contemplation on how the Tao's nature is reflected in all the beauties of existing things, reinforcing the interconnectedness of all aspects of existence with the Tao.

Chapter 22 - The Transformative Power of the Tao

This passage emphasizes the transformative power of the Tao:

It can turn what's partial into something complete.

It can straighten what's crooked.

It can fill what's empty.

It can renew what's worn out.

Additionally, it contrasts the sage's humble and non-competitive nature with the pitfalls of having too many desires. The completeness principle is a reminder that true fulfillment and wholeness are found in aligning with the Tao, which encompasses all transformations and leads to a state of inner and outer harmony.

Chapter 23 - Connecting with Others

This passage emphasizes the importance of aligning with the natural spontaneity of one's own nature and the Tao. It highlights that when one genuinely follows the Tao and stays true to its principles, others who share these intentions naturally gravitate toward them. Even those who may not fully succeed in following the Tao find common ground. However, sincerity and faith in one's alignment with the Tao are crucial for this harmonious connection with others.

Chapter 24 - The Importance of Modesty

In simpler terms, this passage advises humility, modesty, and a lack of self-centeredness. It suggests that excessive self-display, stubbornness, boasting, and self-conceit are seen as unbalanced and undesirable, akin to things that people generally dislike. Those who follow the Tao actively reject and avoid such behaviors in favor of maintaining harmony and balance in their actions and interactions with others.

Chapter 25 - The Hierarchy of Existence

This passage reflects on the profound nature of the Tao as the source of all things. It describes the Tao as formless, eternal, and all-encompassing. Laozi acknowledges that he doesn't know its true name but refers to it as the Tao, emphasizing its greatness. The passage also highlights the interconnectedness of the Tao, Heaven, Earth, and the sage king, as well as the hierarchy of laws governing these entities, with the Tao's law being its inherent nature.

Chapter 26 - Gravity, Lightness, Stillness & Movement

This passage advises leaders, particularly wise rulers, to maintain a sense of balance. They should be grounded and stable (gravity) while also being able to act with agility and decisiveness (lightness). It warns against becoming too complacent or too impulsive, as either extreme can lead to problems in leadership. Balancing gravity with lightness and stillness with movement is key to effective governance.

Chapter 27 - The Skill of the Sage

This passage underscores the value of skill and discretion in various aspects of life. It emphasizes the effectiveness of actions that leave no trace, whether in travel, communication, calculations, or securing things. The sage, too, is skilled in a way that preserves and saves without rejecting. Additionally, it emphasizes the mutual respect and support between skilled individuals and their helpers, highlighting the importance of this collaboration and the sense of mystery it can create.

Chapter 28 - Leaders Avoid Force

In essence, this passage emphasizes the importance of balance, humility, and inclusiveness in both personal character and leadership. It suggests that a wise leader doesn't need to use force but can govern effectively by embracing simplicity, humility, and harmony, much like the uncarved block that becomes a vessel when divided and distributed.

Chapter 29 - The Dangers of Clinging or Grasping

In this passage from the Tao Te Ching, Laozi reflects on the nature of leadership and the dynamics of power. He emphasizes the idea that trying to gain or hold onto power through forceful or active means is counterproductive:

The Ineffable Nature of the Kingdom: Laozi begins by suggesting that if someone desires to obtain a kingdom or power for themselves and tries to achieve this through active, forceful actions, they are unlikely to succeed. He characterizes the kingdom as a "spirit-like thing" that cannot be obtained through aggressive efforts. Instead, attempting to gain power through such means will lead to its destruction, and trying to tightly grasp it will result in its loss.

The Changing Nature of Things: Laozi continues by describing the inherent nature of existence, which is characterized by change and reversals. What was once in front may become behind, what was warm can turn cold, and strength can sometimes lead to weakness. He points out that excessive effort, extravagance, and indulgence can ultimately lead to ruin.

Chapter 30 - Rule in Harmony with the Tao

Overall, this passage advises leaders to avoid the excessive use of force and domination, as these actions can lead to resistance and negative consequences. Instead, leaders should seek harmony, balance, and humility in their approach to governance, aligning themselves with the natural order of things as guided by the Tao.

Chapter 31- The Principle of Non-Violence

Laozi's overall message is that the Tao emphasizes peaceful and harmonious ways of resolving conflicts and disputes. Violence and warfare should be avoided whenever possible, and the superior man should seek victory through means other than the use of force. The passage underscores the importance of aligning with the principles of the Tao, which promote balance, virtue, and the avoidance of unnecessary harm.

Chapter 32 - The Unchanging Tao

The Tao, as an unchanging and nameless essence, is beyond full definition or description.

Despite its subtlety, the Tao possesses great power. If a ruler embodies it, people willingly follow, highlighting the idea that true leadership is based on harmony with the Tao, not force.

The Tao harmonizes Heaven and Earth, providing nourishment and guidance to the world without human intervention.

Once the Tao becomes recognized and named, people can align themselves with its principles, leading to balance and the avoidance of errors.

The Tao is likened to a source that unifies and guides all things, like rivers and streams flowing into larger bodies of water.

In essence, the passage underscores the importance of humility, alignment with the Tao, and the natural harmony it brings to the world.

Chapter 33 - Discernment and Intelligence

“He who knows other men is discerning; he who knows himself is intelligent. He who overcomes others is strong; he who overcomes himself is mighty. He who is satisfied with his lot is rich; he who goes on acting with energy has a (firm) will. He who does not fail in the requirements of his position, continues long; he who dies and yet does not perish, has longevity.”

In summary, this passage encourages self-awareness, inner strength, contentment, and persistence as essential qualities for a meaningful and successful life.

Chapter 34 - The Humility of the Tao

This passage tells us that the Tao is everywhere and is responsible for everything in the world. It doesn't brag about its actions. Instead, it quietly supports and nurtures everything. This humility is a source of great power.

The sage, someone who understands the Tao, also achieves greatness through humility and not seeking dominance. So, it teaches us that being humble and modest can lead to great accomplishments.

Chapter 35 - The Attraction of the Tao

This passage tells us that someone who embodies the Tao, which is like the great image of an invisible force, attracts people from all over the world. When people come to this person, they find refuge, peace, and a sense of ease.

It compares the Tao to music and delicious food that can temporarily captivate someone's attention. However, unlike these fleeting pleasures, the value of the Tao is limitless and inexhaustible, even though it may seem unremarkable at first glance or hearing. It emphasizes the deep and lasting benefits of aligning with the Tao.

Chapter 36 - Subtle Action

This passage describes the principle of subtle and strategic action. When someone intends to do something, they often take a preparatory step in the opposite direction. For example, before taking a breath in, there is usually an exhalation; before weakening someone, they may first strengthen them; before overthrowing someone, they might have raised them up, and before taking something away, they might have given something.

It emphasizes the power of the soft and the weak to overcome the hard and the strong, illustrating that a gentle approach can be more effective than forceful actions.

The passage also advises against revealing certain things prematurely. Just as you shouldn't take fish from deep waters or show valuable tools to the public, some actions or resources should be kept hidden or used strategically for the benefit of the state. This is referred to as "Hiding the light (of his procedure)."

Chapter 37 - The Natural Course of the Tao

This passage highlights the inherent nature of the Tao, which operates effortlessly and without a specific purpose. It doesn't act for the sake of action but simply follows its natural course. As a result, it can influence and transform everything without actively trying to do so.

If rulers, such as princes and kings, could align themselves with the Tao and embody its qualities, their influence would naturally bring about positive transformations in their domain. This is because the Tao operates in a way that allows things to align and harmonize spontaneously.

The passage also emphasizes the idea of desirelessness and simplicity. When one is free from desires and maintains a state of stillness and simplicity, things tend to go smoothly and naturally, as if guided by their own inherent will. This nameless simplicity is considered a state of balance and harmony in alignment with the Tao.

Part 2

Chapter 38 - The Cycle of Society

This passage reflects the idea of a societal cycle often found in Taoist philosophy. It suggests that when the Tao, representing the natural order and balance, is lost or forgotten in society, certain virtues like benevolence, righteousness, and propriety become more prominent as a way to compensate for the loss. However, these virtues can also become superficial and mere appearances without genuine substance. This cycle continues until people return to the true essence of the Tao, emphasizing sincerity and authenticity over external displays of virtue.

Chapter 39 - How the Tao Impacts Existence

This passage explains that the Tao (the One) has a profound influence on various aspects of existence, including:

Heaven: The Tao makes Heaven bright and pure.

Earth: It provides stability and firmness to the Earth.

Spirits: The Tao empowers spiritual beings.

Valleys: It keeps valleys full and abundant despite their emptiness.

All Creatures: All living creatures depend on the Tao for their existence.

Princes and Kings: Even rulers and leaders draw their guidance and models from the Tao.

In essence, this passage emphasizes that the Tao is the source and underlying force behind all aspects of existence, from the natural world to the actions of rulers and kings. It underscores the interconnectedness of everything in the universe through the Tao.

Heaven and Earth: If Heaven were not pure and Earth not firm, they would lose their integrity and stability. This purity and stability are maintained by the Tao. Similarly, spirits depend on the Tao for their powers, and valleys stay fertile through the Tao's influence. Without the Tao, life itself would wither away, and even the moral authority of princes and kings would decay.

This passage underscores the idea that embracing humility and simplicity, rather than appearing grand and imposing, is the path to genuine strength and stability, in alignment with the Tao.

Chapter 40 - The Mysterious Tao

In essence, this passage underscores the mysterious and unpredictable nature of the Tao, from which everything emerges and to which everything returns. It encourages us to embrace the idea that the Tao's ways may not always align with our expectations or conventional wisdom but are, nonetheless, the source of all existence.

Chapter 41 - The Three Types of Scholars

There are three types of scholars. The highest-class scholars take the Tao seriously and try to follow it in their lives. Middle-class scholars are somewhat inconsistent; they sometimes follow the Tao and sometimes don't. The lowest-class scholars find the Tao amusing and laugh at it. The passage suggests that this laughter is actually appropriate because the Tao is not something that can be easily understood or taken lightly.

The Tao is described as hidden and nameless, yet it is skilled at providing what everything needs and making things whole. Essentially, it's a mysterious force that guides and completes everything in the universe, even though we may not fully understand it.

Chapter 42 - The Tao Gives Rise to Everything

In simple terms, this passage explains the concept of how the Tao (the natural way of the universe) gives rise to everything and how certain qualities and titles that people dislike can actually be beneficial:

Creation from the Tao: The Tao first created "One" (a single, undifferentiated state). Then, "One" gave rise to "Two," and "Two" produced "Three." From these three, everything in the world emerged. These things start in obscurity (a hidden state) and move towards brightness (a visible state) while being guided by the balance of emptiness.

Paradox of Titles: People generally dislike being called orphans, having little virtue, or being compared to carriages without wheels (naves). However, kings and princes sometimes use these terms to describe themselves. This paradox means that sometimes, qualities or titles that seem negative can actually lead to growth and improvement.

Teaching from the Tao: The passage concludes by saying that it teaches what others teach, emphasizing that strong and aggressive individuals don't meet a natural end (they often face consequences for their actions). This idea forms the foundation of the teaching.

Overall, the passage highlights the Tao's role in creation, the paradox of titles and qualities, and the importance of following the natural order.

Chapter 43 - The Doctrine of Non-Action

This passage emphasizes the power of softness, non-substantial existence, and non-action:

Softness Triumphs Over Hardness: It suggests that the softest things in the world can overcome the hardest. This means that flexibility, gentleness, and adaptability often prevail over rigid and forceful approaches. Similarly, something with no substantial existence can enter where there's no opening or resistance. This implies that subtleness and the absence of physical presence can achieve things that forceful actions cannot. The passage concludes that understanding these principles reveals the advantage of doing nothing with a specific purpose or not forcing things.

Rare Attainment: The passage acknowledges that very few people in the world truly grasp the teachings of non-action and the benefits it brings. This highlights the idea that embracing a more passive and harmonious approach to life is not common, as many people are inclined toward active and forceful behaviors.

In essence, this passage encourages us to appreciate the power of softness, subtlety, and non-action in achieving favorable outcomes, which are often underestimated in a world that values action and assertiveness.

Chapter 44 - Contentment, Simplicity and Modest Living

Or fame or life,

Which do you hold more dear?

Or life or wealth,

To which would you adhere?

Keep life and lose those other things;

Keep them and lose your life:—which brings

Sorrow and pain more near?

Thus we may see,

Who cleaves to fame

Rejects what is more great;

Who loves large stores

Gives up the richer state.

Who is content

Needs fear no shame.

Who knows to stop

Incurs no blame.

From danger free

Long live shall he.

This passage explores the idea of prioritizing different aspects of life and their consequences:

Fame or Life: It starts by posing a question about what we value more: fame or life. Do we hold our reputation and recognition in high regard, or do we cherish our existence above all else?

Life or Wealth: The passage then extends this question to life versus wealth. Would we cling to life even if it meant losing our material possessions, or would we prioritize our wealth over our very existence?

The Outcomes: It presents two scenarios:

If you choose to keep your life but forfeit fame, wealth, or other things, you may experience sorrow and pain because you've lost what you held dear.

On the other hand, if you cling to fame, wealth, or other external things at the expense of your life, you are risking your well-being and safety.

Contentment and Moderation: The passage concludes by highlighting the value of contentment and moderation. It suggests that those who are content with what they have need not fear shame or blame. They can live free from danger and enjoy a long life.

In essence, this passage encourages us to reflect on our priorities and reminds us that sometimes, the pursuit of external rewards like fame and wealth can come at the cost of our well-being and even our lives. It underscores the importance of balance, contentment, and knowing when to stop in our desires and ambitions.

Chapter 45 - Balance, Humility and Moderation

This passage conveys the idea of balance, humility, and moderation:

Humility in Achievements: The passage suggests that someone who regards their great achievements as insignificant or unimportant will maintain their vitality and strength over a long period. In other words, staying humble and not boasting about one's accomplishments contributes to enduring energy and vigor.

Constant Action and Stillness: The passage goes on to suggest that maintaining a balance between constant action and stillness is essential. Constant action can help overcome cold, while being still can overcome heat. Furthermore, purity and stillness provide the correct guidance for all under heaven, implying that finding equilibrium between activity and rest leads to a harmonious and balanced life.

Chapter 46 - The Sufficiency of Contentment

“When the Tao prevails in the world, they send back their swift horses to (draw) the dung-carts. When the Tao is disregarded in the world, the war-horses breed in the border lands. There is no guilt greater than to sanction ambition; no calamity greater than to be discontented with one's lot; no fault greater than the wish to be getting. Therefore the sufficiency of contentment is an enduring and unchanging sufficiency.”

In summary, this passage encourages living in accordance with the Tao, appreciating simplicity, and finding contentment in one's current circumstances rather than constantly pursuing ambition and material gain.

Chapter 47 - True Wisdom is gained from Within

“Without going outside his door, one understands (all that takes place) under the sky; without looking out from his window, one sees the Tao of Heaven. The farther that one goes out (from himself), the less he knows. Therefore the sages got their knowledge without travelling; gave their (right) names to things without seeing them; and accomplished their ends without any purpose of doing so.

In essence, this passage encourages a contemplative and introspective approach to gaining wisdom and understanding. It suggests that true knowledge can be found within oneself and in observing the natural world, rather than in constant external pursuits or travels.

Chapter 48 - The Doctrine of Non-Doing

the passage highlights the idea that those who seek knowledge may accumulate more information over time, but those who follow the Tao seek to simplify their lives and actions, ultimately arriving at a state of non-action where they effortlessly align with the natural order of the universe. It suggests that true wisdom comes from embracing the flow of life and not striving to control or accumulate.

Chapter 49 - The Disposition of the Sage

This passage portrays the sage as a humble and virtuous figure who adapts their mindset to align with the people they interact with. They lead by example through goodness and sincerity, influencing others to embody these qualities. The sage's appearance of indecision and indifference underscores their role as a wise and impartial guide for those seeking wisdom and guidance.

Chapter 50 - Walk the Middle Path

This passage emphasizes the importance of balance and moderation in one's approach to life. It suggests that excessive efforts to extend life can be counterproductive and lead to negative outcomes. Instead, skillful management of life allows individuals to navigate life's challenges with confidence and without fear.

Chapter 51 - The Nurturance of the Tao

This passage explains the natural flow and nurturing quality of the Tao in the creation and development of all things. Everything in the world honors and benefits from the Tao's operation spontaneously, without any imposed rules or commands. The Tao guides, nourishes, and supports all things without asserting ownership or control, and this process is described as its mysterious operation.

Chapter 52 - The Inner Light of the Tao

This passage emphasizes the Tao as the source, likening it to a mother who nurtures all things. It suggests that understanding one's connection to the Tao is essential for a safe and harmonious life. By maintaining inner qualities associated with the Tao, such as simplicity and softness, one can avoid unnecessary exertion and trouble. The passage concludes by highlighting the importance of using one's inner light wisely and returning to the source, which leads to clarity and protection from harm.

Chapter 53 - Avoid Ostentation

This passage warns against boastful displays of power and wealth. It suggests that if the speaker were to suddenly gain authority and govern according to the Great Tao (the way of harmony and balance), their greatest fear would be falling into the trap of pride and ostentation.

It then contrasts the simplicity and balance of the Great Tao with the behavior of certain rulers who prioritize luxury, excess, and outward displays of wealth and power. These rulers neglect the well-being of their people and their lands, leading to a state of imbalance and emptiness. Such rulers are characterized as robbers and boasters, as their actions go against the principles of the Tao.

Chapter 54 - The Tao’s Effect on Society

This passage emphasizes the positive effects of nurturing the Tao within oneself and applying it in various contexts, from personal to societal:

It begins by describing how the Tao, when skillfully cultivated within an individual, becomes unshakable and provides protection. What is embraced by the Tao cannot be taken away or lost. This leads to a succession of generations paying homage to the wisdom and balance it represents.

The text then explains that when the Tao is nurtured within oneself, it brings true vitality and richness. When it influences a family, there is prosperity. When it extends to the neighborhood, abundance prevails. And when it spreads throughout the state or kingdom, good fortune is widespread.

The effects of the Tao are observed at different levels, from individual to society, and it brings positive results.

The passage concludes by affirming the certainty of these effects, stating that the method of observation confirms the Tao's sure influence throughout the world.

Chapter 55 - The Harmony of the Tao

This passage emphasizes the harmony of the Tao and its natural balance:

Those in harmony with the Tao are like infants, unaffected by external threats.

Strength comes from balance, not force.

Understanding harmony leads to wisdom and recognition of the Tao.

Anything contrary to the Tao ultimately declines and ends.

Chapter 56 - The Mysterious Agreement

Those who truly understand the Tao don't talk about it, while those who talk about it often don't truly understand it. True understanding leads to humility and the ability to adapt to others. This is referred to as 'the Mysterious Agreement.' A person in this state transcends worldly distinctions and is considered the noblest of individuals.

Chapter 57 - Governing a State through Non-Action

This passage emphasizes the idea that a state or kingdom is best governed through a sense of non-action and non-interference:

While a state can be ruled through correction and weapons, true ownership and harmony of a kingdom come from not imposing excessive actions or purposes on the people.

The text highlights the consequences of excessive regulations and actions: increased poverty, disorder, strange contrivances, and the rise of criminals.

The sage's approach is to refrain from deliberate interference and ambition, allowing the people to naturally transform, become correct, and attain simplicity on their own. This illustrates the power of non-action in effective governance.

Chapter 58 - Libertarian Governments

“The government that seems the most unwise, Oft goodness to the people best supplies; That which is meddling, touching everything, Will work but ill, and disappointment bring.”

Good Governance: It suggests that a government that appears unwise to the people can often provide the best outcomes for them. Such a government may not meddle in every aspect of people's lives, allowing them a degree of freedom and self-determination. This approach is seen as providing happiness and contentment.

Caution with Correction: The passage raises the question of whether correction or intervention is necessary in governance. It warns that excessive correction can lead to distortion and unintended negative consequences. People may be deluded into thinking that constant meddling and correction are necessary for good governance.

Sage-like Governance: The sage, or wise leader, is depicted as one who governs with balance and moderation. They are straightforward and bright in their approach to governance but avoid excesses. They do not harm or oppress the people but provide leadership that is fair, transparent, and not overbearing.

Chapter 59 - Moderation in Governance

This passage emphasizes the importance of moderation in governance and personal conduct:

Moderation in Governance: The text suggests that moderation is crucial for governing human affairs and maintaining harmony with the heavenly or natural order. It implies that excessive measures or extremes are not effective in achieving these goals.

Early Return and Accumulation of Attributes: The concept of "early return" refers to returning to a state of balance and harmony. This early return is achieved through the repeated accumulation of attributes associated with the Tao, which represents the natural way or principle. These attributes, when accumulated, help in overcoming obstacles and challenges. The passage also suggests that the potential benefits of such subjugation or control are limitless, and a ruler who understands this principle can effectively govern a state.

Possessing the Mother of the State: The passage concludes by stating that someone who possesses the "mother of the state" can have a long-lasting influence. This metaphorical language implies that a leader who embodies the principles of moderation and harmony can lead a state to stability and longevity, much like a plant with deep roots and sturdy stalks symbolizes enduring life.

In essence, the passage advocates for moderation as a fundamental principle in governance and personal conduct, highlighting its potential to bring about lasting harmony and stability in society.

Chapter 60 - Harmony with the Spirit world

Cooking Small Fish Analogy: Governing a great state is likened to the art of cooking small fish. Just as one must handle small fish delicately to prevent them from falling apart, governing a large state requires careful handling and moderation.

Governance According to the Tao: When a state is governed in accordance with the Tao, the spiritual energy of departed souls is not manifested in a harmful way. This suggests that when the state is aligned with the natural order, there is no need for the departed spirits to cause harm. Additionally, a wise ruler following the Tao does not harm people.

Mutual Harmony and Virtue: When the state and the spiritual realm do not harm each other, their positive influences converge and contribute to the virtue associated with the Tao. This implies that a state that governs wisely and in harmony with the Tao can achieve a state of balance and virtue.

Chapter 61 - The Power of Stillness

Analogy of a Great State: A great state is compared to a low-lying, down-flowing stream that becomes the central point to which smaller states naturally gravitate.

Female and Stillness Analogy: The analogy of females and stillness is used to illustrate how the small or submissive can exert influence. The female's stillness is considered a form of humility or abasement, but it can lead to dominance.

Relations Between States: The passage suggests that a great state gains the allegiance of smaller states by showing humility and welcoming them. Conversely, smaller states can win the favor and protection of a great state by humbling themselves and offering their service. Both sides achieve their desires through a mutual relationship, but the great state must be willing to lower itself to make these connections.

Chapter 62 - The Honor and Inclusiveness of the Tao

In summary, this passage underscores the exceptional value of the Tao, not only for its ability to bring honor and virtue but also for its inclusive nature, offering guidance and transformation to all who seek it, regardless of their past actions or character.

Chapter 63 - Great things from Small Beginnings

“All difficult things in the world are sure to arise from a previous state in which they were easy, and all great things from one in which they were small. Therefore the sage, while he never does what is great, is able on that account to accomplish the greatest things.”

This passage explains the principles of the Tao, emphasizing simplicity, anticipation, and the sage's approach to life:

Effortless Action: The Tao encourages acting without conscious effort, conducting affairs without feeling burdened by them, and experiencing life without being overly concerned with sensory details. It suggests treating small matters as significant and few as many, as well as responding to injury with kindness.

Anticipation and Timing: The master of the Tao possesses the ability to anticipate challenges when they are still easy to address and undertake significant actions when they appear small. This wisdom recognizes that many difficult and great things often emerge from simple and easy beginnings. By not striving for grandeur, the sage is able to accomplish the greatest deeds.

Seeing Difficulty: The passage advises against lightly promising or assuming that things are easy, as this can lead to a lack of faith and unexpected challenges. The sage, on the other hand, approaches even seemingly easy tasks with an awareness of potential difficulties. By doing so, the sage is prepared for challenges and, as a result, encounters fewer difficulties.

Chapter 64 - A Thousand Mile Journey Begins with a Single Step

“That which is at rest is easily kept hold of; before a thing has given indications of its presence, it is easy to take measures against it; that which is brittle is easily broken; that which is very small is easily dispersed. Action should be taken before a thing has made its appearance; order should be secured before disorder has begun.”

The passage highlights the idea that it is easier to deal with situations when they are still in their early stages or before they become apparent. Things at rest or in their initial states are easier to manage and control. Brittle things are more prone to break, and small things are easily scattered. Therefore, the text advises taking action and establishing order proactively, before disorder emerges.

“The tree which fills the arms grew from the tiniest sprout; the tower of nine storeys rose from a (small) heap of earth; the journey of a thousand li commenced with a single step.”

A towering tree begins as a tiny sprout, a tall tower starts as a heap of earth, and a thousand-mile journey begins with a single step. This reinforces the idea that small, consistent actions can lead to significant outcomes.

“He who acts (with an ulterior purpose) does harm; he who takes hold of a thing (in the same way) loses his hold. The sage does not act (so), and therefore does no harm; he does not lay hold (so), and therefore does not lose his hold. (But) people in their conduct of affairs are constantly ruining them when they are on the eve of success. If they were careful at the end, as (they should be) at the beginning, they would not so ruin them.”

The passage concludes by noting that many people tend to ruin their endeavors just as they are about to succeed. This happens because they may become careless or complacent when they are close to achieving their goals. The text implies that if people were as cautious and attentive at the end as they were at the beginning, they could avoid these self-sabotaging mistakes.

“Therefore the sage desires what (other men) do not desire, and does not prize things difficult to get; he learns what (other men) do not learn, and turns back to what the multitude of men have passed by. Thus he helps the natural development of all things, and does not dare to act (with an ulterior purpose of his own).”

The sage is said to desire what other people do not desire. This means that the sage values things that are often overlooked or undervalued by others. Instead of seeking what is commonly considered valuable, the sage finds worth in simplicity, humility, and the natural order of things. This desire for the overlooked and unpretentious aligns with the Tao's principle of embracing the unadorned and ordinary.

Chapter 65 - The Mysterious Excellence of a Governor

Lao Tzu begins by referring to the ancient leaders who practiced the Tao. He suggests that their purpose in practicing the Tao was not to enlighten or educate the people in a traditional sense. Instead, their aim was to keep the people simple and ignorant. This may seem counterintuitive, but it aligns with the Taoist principle of valuing simplicity and naturalness. The idea is that by keeping people simple and ignorant of unnecessary knowledge or desires, they are more likely to live in harmony with the Tao and avoid unnecessary complications.

Lao Tzu acknowledges that governing people can be challenging, especially when they possess a lot of knowledge. When a ruler or leader tries to govern a state using their wisdom or knowledge, it can lead to unintended consequences and difficulties. This is because attempts to control and micromanage can disrupt the natural flow of things and create resistance among the people.

Lao Tzu suggests that a wise ruler understands the balance between governing and allowing things to unfold naturally. This understanding constitutes the "mysterious excellence" of a governor. Such a governor doesn't rely solely on their knowledge but rather on an innate sense of how to lead without imposing too much control. By embodying this mysterious excellence, a leader sets an example for others and leads them to conform to a greater harmony.

Chapter 66 - Great Leaders Abase Themselves

In summary, this passage emphasizes the concept of effective leadership through humility and non-contention. It likens the skill of great leaders to that of rivers and seas, which receive the tribute of smaller streams because they are lower. The sage ruler, seeking to lead effectively, places himself below others in words and behind them in person. This approach allows him to lead without imposing his weight or causing harm. As a result, people admire and exalt him, and no one dares to contend with him due to his non-striving nature.

Chapter 67 - Gentleness, Economy & Humility

This passage emphasizes the value of three precious qualities:

Gentleness: The Tao is considered great because it may appear inferior due to its gentle nature. Gentleness is praised as a virtue that allows one to be bold when necessary.

Economy: Being economical or frugal is also highly regarded. It enables one to be generous when needed.

Shrinking from taking precedence: Humility, or the willingness to step back and not always seek to be first, is seen as a virtue that can lead to the highest honor.

These qualities are contrasted with the tendencies of many people to prioritize boldness over gentleness, generosity over economy, and always seeking to be first over humility. The passage suggests that embracing gentleness, economy, and humility can lead to victory and protection.

Chapter 68 - The Tao Warrior

“He who in (Tao's) wars has skill Assumes no martial port; He who fights with most good will To rage makes no resort. He who vanquishes yet still Keeps from his foes apart; He whose hests men most fulfil Yet humbly plies his art. Thus we say, 'He ne'er contends, And therein is his might.' Thus we say, 'Men's wills he bends, That they with him unite.' Thus we say, 'Like Heaven's his ends, No sage of old more bright.'“

This passage conveys the idea that a skillful leader who follows the principles of Tao approaches conflict and leadership in a unique and effective way:

A skillful leader doesn't display a martial or aggressive demeanor even in times of war or conflict.

Instead of resorting to anger or rage, they approach conflict with goodwill and composure.

They may achieve victory but do not engage in unnecessary confrontation with their foes.

Even though they give commands and people follow them, they do so with humility and without arrogance.

The passage emphasizes that such a leader doesn't engage in direct confrontation but achieves their goals through subtlety, unity, and a deep understanding of Tao. Their approach is seen as powerful, aligning with the way of Heaven and surpassing the wisdom of past sages.

Chapter 69 - Just Warfare

“There is no calamity greater than lightly engaging in war. To do that is near losing (the gentleness) which is so precious. Thus it is that when opposing weapons are (actually) crossed, he who deplores (the situation) conquers.”

The master of war prefers a defensive stance over an offensive one. They are cautious and do not rush into hostilities. They prioritize retreating over advancing, symbolically "advancing against the enemy where there is no enemy." This approach involves careful preparation and not provoking conflict unnecessarily.

Engaging in war too lightly is considered a grave mistake. It can lead to the loss of the valuable quality of gentleness. The passage suggests that it is better to regret the situation and seek peaceful solutions than to rush into conflict.

Chapter 70 - The Difficulty of the Path